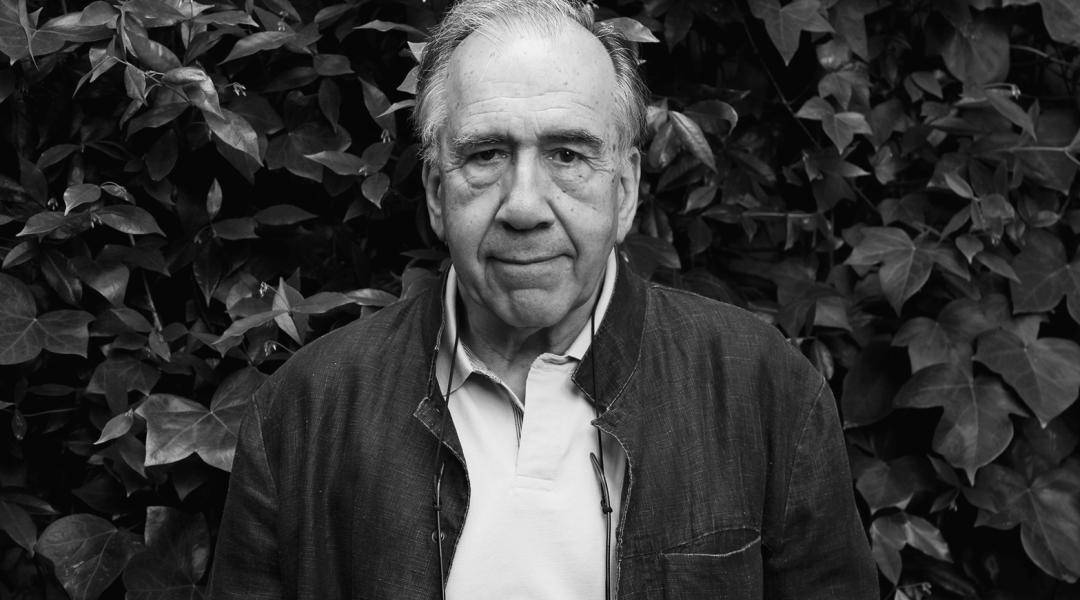

Joan Margarit

The Poet of Clarity

There are poets whose existence protects us from the vanities of literature and reconciles us with the troubles of life. One such poet is the winner of the latest Miguel de Cervantes Prize, Catalan writer and architect Joan Margarit (Segarra, 1938), author of such important books as ‘Joana’, ‘Cálculo de estructuras’, ‘Casa de Misericordia’ or ‘Se pierde la señal’.

At 81, Margarit’s writing exudes a passion and excitement for poetry that can only be compared to those expressed by his magnificent voice, which the audience has the privilege of enjoying during the jazzy poetry recitals that he offers across the country with enviable pizzazz. This master, oblivious to generations and chapels, is convinced of the healing powers of poetry as an “instrument of solace before the sorrow of human existence”. On April 23 in Alcalá de Henares, their Majesties will present him with an award recognising his career as a “deeply meaningful poet of clear language that has enriched both the Spanish and Catalan languages”. He speaks to Talento a bordo about this.

Have you thought about your speech during the Miguel de Cervantes Prize ceremony?

Not yet, but I can already tell you that a part of my speech is always written in prose, and the other, as a poem. It’s not a speech in verse, just that I incorporate poetry into my recital.

Why do you write poetry?

Because poetry is one of the most convincing instruments we have as human beings to give solace to our sorrows. When faced with any setback in life, from abandonment to death, we have nothing more than the life vest made by those who love us and console us. But this doesn’t stop us from ending up alone with our sorrows.

And who consoles sorrow in solitude?

You distract yourself; for example, you can go and see a football match. But I wouldn’t recommend it; after an hour and a half, you’ll be worse off. Poetry and music are tools of solace. That’s why I write: to make tools of solace for others.

“Poetry and music are tools of solace. That’s why I write: to make tools of solace for others”

Do poets need to be recognised for their poetry to exist?

An award helps more people to find out that poetry exists as a tool, so that more people use it.

Although they are very faithful, why do you think there are so few readers of poetry?

In the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque period, there were many. It is from Romanticism onwards that bad poets declared that poetry was hard, that you needed a special spirit, to be a suicidal romantic. Then, avant-garde poets made it even harder by writing unintelligible poems. Between them all, during a long period of time, poetry lost its main attributes. It wasn’t until post avant-garde realism that the simple, important role of poetry was recovered, without the need to prepare for reading a poem. Poetry didn’t begin its comeback until the mid-20th Century.

Does the fact that many poets only write poetry for other poets contribute to this deterioration?

A poem must be understandable. An ordinary person must be able to understand a poem. If you read it once, you can miss many things, but if you read it ten times, you’ll understand much more. Like with everything in life. A poem that you have read ten times and haven’t understood is bad poetry.

“A poem that you have read ten times and haven’t understood is bad poetry”

Besides rhythm, what is the essence of a poem?

I don’t know. I don’t know why a poem fulfils its purpose at any given time. You write a poem in fourteen or ten verses, and someone you don’t know reads it 5,000 km away. For whatever reason, that person is suffering from a dreadful sorrow and when they read it, it comforts them. It’s almost a miracle. Nobody knows why. None of the volumes written by scholars, experts and professors has cleared this up.

After infancy, maturity and old age “comes the ultimate truth, hard and simple”. Aren’t you getting ahead of yourself?

No, no. Life has two singular opposites, infancy and old age. In the middle is a necessary, giant mess. The same that makes you interview me, the professor teach children, the market open in the morning, the bus need a driver and for them to not oversleep. This is the power of that mess, but it’s still a mess.

Structure calculation, in Architecture, aims for the greatest resistance and stability with the least amount of material. Your poetry also tries to say the most with the least amount of words. Has your training as an architect determined your style?

Absolutely. I’m the result of my own life and training. Poetry has a lot of common sense. To talk about poetry, you don’t need to have a white beard or be a monk or a wise man. Common sense is enough. All I ask from a reader of poetry is common sense.

“To talk about poetry, you don’t need to have a white beard or be a monk or a wise man. Common sense is enough”

Your book Para tener una casa hay que ganar la guerra (Austral, 2018) is a collection of some of your experiences from your childhood and young adulthood. Will there be a sequel?

No, because it’s not a memoir. It’s the answer to why I’ve written the poems I’ve written and not others. If this book were just my story until the age of 20, it would be four times as long. It includes the experiences that are related to the poems I’ve written, not the reason for each one. That’s what that book aims to answer.

Does not belonging to a generation make you feel isolated, or do you think it’s an advantage?

It makes me feel free. It’s an advantage because it makes things harder for fibbers and tricksters.

Do you feel suffocated by the Spanish language, despite never hating it?

It did suffocate me at one point, for example, when I was forbidden to talk in Catalan. My first memory at the age of four was a smack from a guard telling me to “speak Spanish”, because I was walking to school with a friend and we were talking in Catalan. It was forbidden at school. This Iberian Peninsula has seen many atrocities. It’s barbaric. Like not pulling the dead out of ditches. We’re the second country, after Cambodia, with the most dead bodies in ditches.

Your book Un asombroso invierno / Un hivern fascinant (Visor, 2018) has also become a dramatic, musical and theatrical show.

For the last thirty years, I’ve always read my recitals with jazz, accompanied by music bands. Instead of singing, I read poetry. It’s something I’ve done for many years with Perico Sambeat (jazz saxophonist), poet Pere Rovira and now with my son Carles, who is a saxophonist and jazz composer, and Albert Bové, who is a great pianist. Music and poetry are an inseparable part of my life.