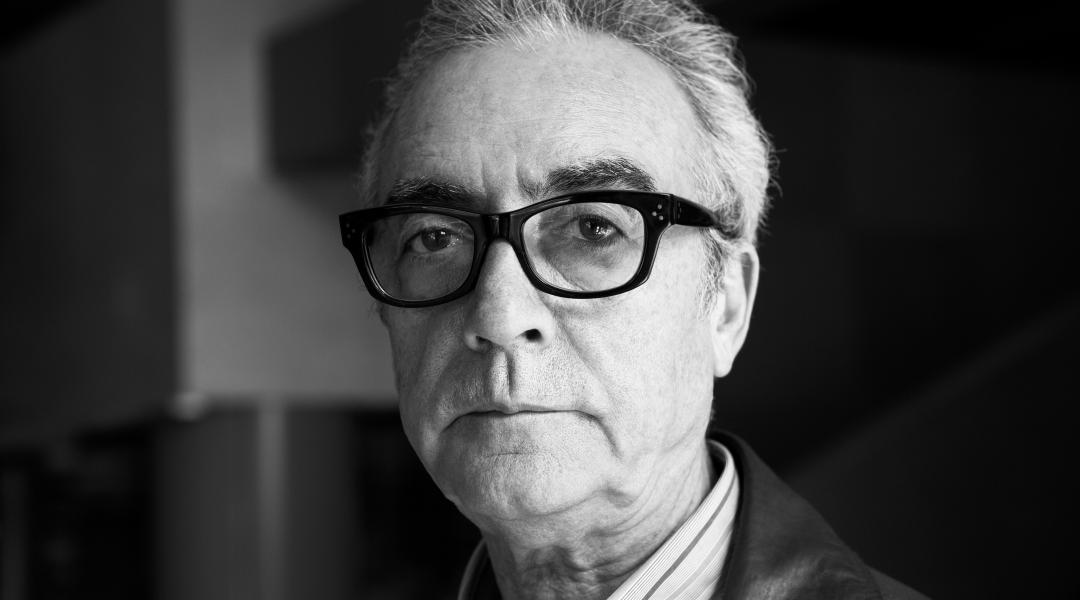

Juan José Millás

The Endless Act of Writing

Inventive, bright, subtle or Kafkaesque are some of the most common qualifiers used to describe the narrative pulse and universe of Juan José Millás, a key figure in both Spanish journalism and contemporary fiction. With a new book under his arm, he is also one of the leading voices in this year’s Festival Eñe.

Any of the columns he has published every Friday for more than 30 years in El País proves his ability to tell stories is beyond doubt. Generations and generations of readers have grown up reading his articles, reports, and novels. Any everyday fact entering his mind is worth being narrated. Any trivial formality becomes in his hands a vital experience of prime importance; in other words, an adventure. So much so that he had to create a literary genre tailored to his talent: the ‘articuento’ (a word combining ‘article’ and ‘cuento’, which translates as short story), a scenario in which imagination is often surpassed by reality.

Life for Juan José Millás (Madrid, 1952) provides very appropriate material for fiction. He will be speaking about this on 16 November at the Fernando de Rojas Theater, in Madrid, at the Festival Eñe 2019, a great celebration of literature in which he is one of the most prominent guests. It is no accident that his talk, alongside writer Manuel Vilas, is titled “La familia, bien, gracias” (Family? All well, thanks.)

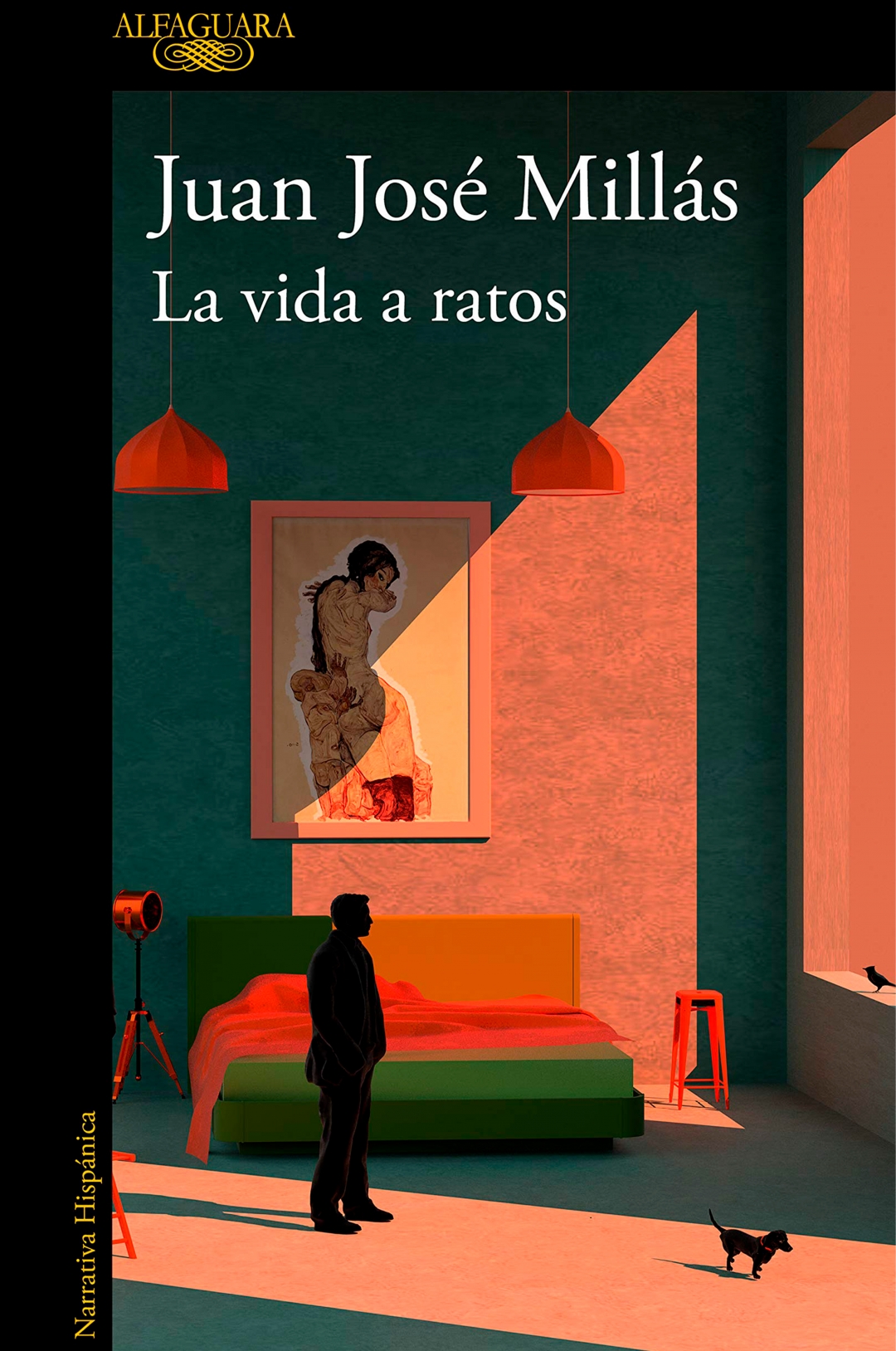

Millás, who once understood that writing — like the scalpel his father kept in his workshop of electromedical devices— heals wounds by opening them, has also dared to write a diary that reads like a novel: La vida a ratos ( Alfaguara), a book in which he again deploys his creative talent by fusing the bland and the extraordinary, and which bears his unmistakable hallmark.

The beginning of your book reminded me of these words by Jules Renard: "You start getting old the day you say: ‘I've never felt younger.’” How do you feel today?

I feel good. I arrived yesterday from Mexico, exhausted, and have slept twelve hours straight. Then I went for a walk in a park near my house and the morning’s chilly air has stimulated me a lot. I went back home with today’s newspapers under my arm and read them while having green tea. In short: I feel completely repaired.

Some writers say they write to avoid seeing a psychoanalyst. Is this your case?

In general, writers are cautious about psychoanalysis, partly because nobody knows exactly what it is. Many fellow writers have told me that they fear to waste the energy they need to write on the couch. But it is the other way around. Psychoanalysis doesn’t close wounds, it opens them. It multiplies your associative capacity, which is critical for writing. “A writer,” said Sábato, “is that who discovers that the Moon, which does not fall, and the stone, which does fall, are the same thing.”

Did you become a writer because you had no choice?

I became a writer because, previously and by chance, I had become a reader. There are no great differences in temperament between the reader and the writer. Moreover, you start reading for the same reasons you start writing, because something between you and the world isn’t working as it should.

“I became a writer because, previously and by chance, I had become a reader”

What do you think about creative writing workshops to train writers?

If we find it reasonable that someone who wants to study music goes to a music conservatory, and that someone who wants to paint enrols in a Fine Arts school, why do we still find it strange that somebody who wants to write joins a writing workshop? You can learn to write, and everything that can be learned can be taught. If there had been writing workshops when I was younger, I would definitely have enrolled in one.

Have you learned more about yourself by reading or by writing?

The combination of the two has brought me closer to the most inaccessible areas of myself and the world. Without reading, there is no writing. Reading is the fuel for writing. You can’t be a writer without being a compulsive reader.

You mention a large number of diseases in your new book, perhaps as a symptom of a somewhat hypochondriacal society. Do you believe in the therapeutic power of writing?

I’m not a hypochondriac, but I act as such because people like it, and I don’t want to disappoint. Writing as therapy? I don’t know. It depends on what you want to heal.

Cover of 'La vida a ratos', by Juan José Millás (Alfaguara, 2019)

You have a splendid memory. You remember being ill with chickenpox when you were a boy as it had happened yesterday? Is memory your best weapon when it comes to writing?

Memory, like the associative capacity I referred to earlier, is essential for a writer. Trying to write without it is like pretending to play tennis without arms.

You are one of Spain’s most prolific writers and journalists. How important are methodology and perseverance in your career?

Discipline and routine are my weapons. You have to write every day, during office hours, even if you have a headache, are haunted by economic or emotional problems or have not slept well. It has often been said that novels are a genre for the clumsy. This forces you to go to work whether it rains or snows and place a brick on top of another with constancy and method. Journalism also demands high degrees of rigor. You can't be a Sunday journalist.

“Without reading there is no writing. Reading is the fuel for reading. You can't be a writer without being a compulsive reader”

You make it clear that you read poets such as Idea Vilariño. Is poetry a "sacred" genre to you?

The most you can hope for in life is to be a poet. The gods speak through them. Poetry is to mysticism what asceticism is to the novel.

You speak of reality as a mystery. Where do you think are the doors to access it?

Reality is not just that piece of cake we call reality. Dreams are reality, delusions are reality, fantasies are reality, desires are reality. The subatomic world is reality. Ambitions are reality. We call reality only what is outside our minds, everything that can be seen and touched. The fantasy genre is realistic in the same way that abstract painting is figurative. Everyone must find their own door to move between clarity and light, between the tangible and the mysterious.

What do you think about the difference between fiction and nonfiction, which so much is being talked about, considering that you cultivate both?

The boundaries between fiction and nonfiction are more rhetorical than they are real. The only thing that differentiates a story from an article is that the materials used in an article come from outside, but the way you select and articulate them coincides with how you select and articulate the materials for a short story.

“Everyone must find their own door to move between clarity and light, between the tangible and the mysterious”

In your new book you say you watch more TV series than films. What are you watching now?

I go to the cinema a lot, too. I’ve just started a TV series that is rather interesting: Mindhunter, about the first psychological studies of serial killers.

How does Juan José Millás see the world today?

Wow! What a question! I think that, despite globalization, we have a very fragmented perception of the world. I don’t see a common thread bringing together all the news we watch on TV or read on newspapers. We live in a world of disjointed data. We confuse data with information, but information is only possible when data creates meaning.