Pilar Aymerich

An ethical gaze

Since her beginnings, at the end of the 1960s, until today, Pilar Aymerich has photographed our social reality with a female gaze steeped in ethics, commitment, and respect for the world and her subjects. Feminist demonstrations and more intimate and traditional portraits make up some of her most iconic images, which won her the Spanish National Photography Award in 2021.

For photographer Pilar Aymerich (Barcelona, 1943) “bad photography” shouldn’t exist, because you can choose not to take it. Honesty, sorority, and morality have gone hand in hand with each negative she has developed in her lab as a silent chronicler of the history of this country. Her work, part of collections like the Museo Reina Sofía, has received the recognition of the 2021 Spanish National Photography Award and the 2005 Creu de Sant Jordi, among other awards, which highlight her commitment to human rights, culture, and femininity.

When you were little, your father used to say that “you had the gaze of an owl.” What was that gaze like?

I was a really shy child and I had quite a solid inner world: I loved reading and making up stories. My father used to say: “This girl does a lot of looking but not much talking, she’s like an owl.” And that stayed with me. At that time, photography wasn’t important to me, although my father had a little Voigtländer camera that he took family photos with. It’s the one I took with me to London when I was 18 or 19 because I didn’t have enough money to buy myself one, and that’s when I started to become the “owl” that looked through the camera.

After studying stage direction and set design: what’s more important to you in a photo, composition or intuition?

In my photographs, I take care of the staging. For example, the people I photograph are always within a natural setting that helps you understand who that person is. I believe that framing is a stage performance; even in demonstrations, when I impress the negative, I see a story behind it.

“As a man, I would never have had to choose between my profession or children. I did, I chose my profession”

What is your creative process like? How do you take on the scene you are going to photograph?

Often times, more than social events, I looked for portraits: the faces of people who were demonstrating. My goal was to tell the story, through those images, of what was happening at the time; the attitude they had, especially the women, when protesting. This involves a gaze. I took photos at so many women’s demonstrations because I was part of the feminist collective that started forming in the 1970s: female writers, painters, photographers... Franco was still alive, and we were fighting to bring theory to feminism. We had to start from scratch.

Was it hard to be a woman and a photographer at that time?

When I covered demonstrations and the police charged against protesters, being a woman and, therefore, invisible was an advantage so that they would walk on. When they started charging, I could stand in a corner, pull out my compact and pretend to touch up my make up or put on lipstick. I don’t run, or climb trees, or throw myself on the ground: I take a more intimist portrait, not so much of the defining moment. I think that being a woman sets your gaze and allows you to connect with others.

What sacrifices have you had to make to live off your vocation?

As a man, I would never have had to choose between my profession or children. I did, I chose my profession. Despite how hard it can be at times, in the 50 years I’ve been doing it I’ve never considered quitting... Well, 20 or 25 years ago I was sick of having my photos cut or not being able to sign them, and I thought about doing “photographic objection”. It bothered me to not receive recognition or respect.

How did that series of female prisoners at the Trinitat prison come about?

One of the demonstrations I covered in 1976 was against the removal of the nuns who ran the Trinitat prison in Barcelona, to be replaced with female civil servants. There were women who’d been completely forgotten, and I wanted to know what they were like, how they were. Two years later they did a small prison reform and removed the nuns. Before the female civil servants arrived, the prisoners themselves took charge of the prison. I worked at Vindicación feminista magazine and was able to get in. For these kinds of reports, it’s emotions that count, the fact that you yourself can become an image of tenderness so that people let you photograph them.

“The worst you can do is betray yourself, that’s why ethics in photography is key”

Is taking or not taking a photograph also a moral decision?

Without a doubt. Documentary photography works with human beings: it’s a relationship between the person in front of and behind the camera. What you are and what you believe in play a role. The worst you can do is betray yourself, that’s why ethics in photography is key. You should never cross the red lines you’ve put down because you’d be lost, you’d jeopardise your morality.

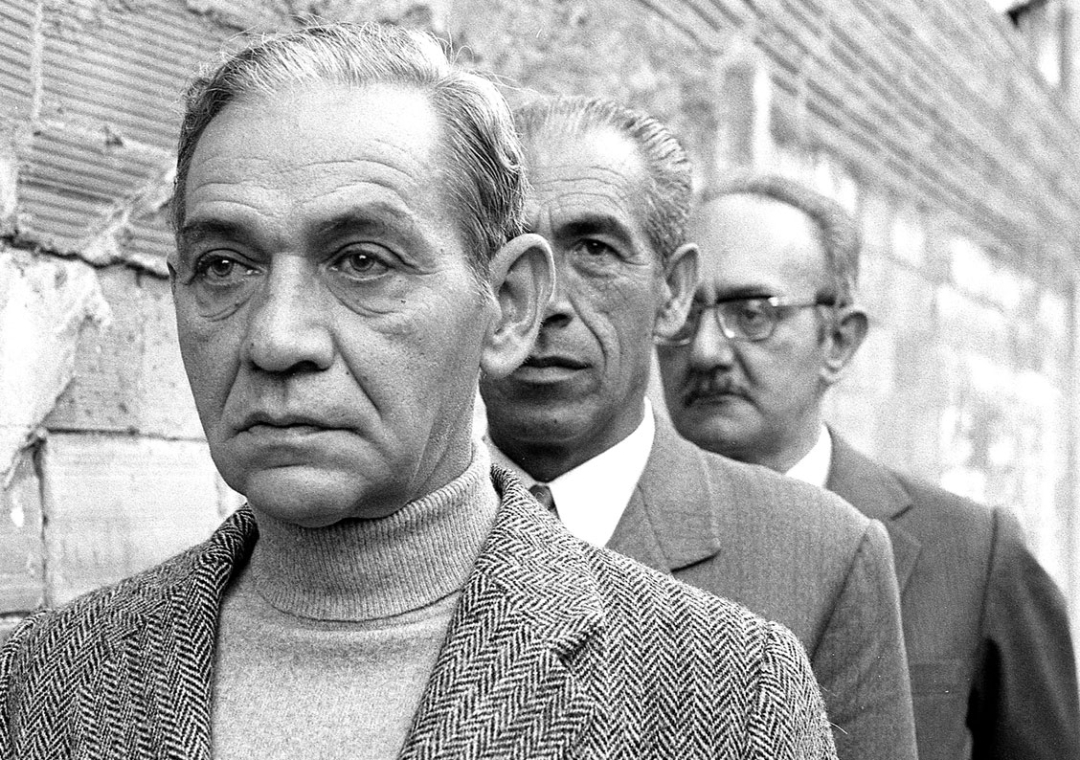

How did you go about taking the portraits of the three Mauthausen survivors?

That day, journalist Montserrat Roig called me to ask me to go to her house, where she was interviewing three men who’d survived the concentration camp. They were telling terrible stories around a table, but I didn’t take that photo, not even as a device, because it didn’t tell a story. When they finished, I asked them to come with me to a nearby piece of waste ground and pose next to a wall. When I suggested that they stand in single file, like at the camp, that was when their faces reflected the pain they felt. I didn’t want to gloat; I just took two photos because I didn’t want them to suffer. Perhaps I’m not a good events photographer because I prefer to lose a shot than to cause pain.

“Perhaps I’m not a good events photographer because I prefer to lose a shot than to cause pain”

Do you believe photographic talent is something you are born with?

You can’t be categorical about this. It’s true that to work with images you need to have a certain gaze. Sometimes it seems like knowing the technique, having a good camera, and being impulsive is enough. But that’s not the case. I think culture is more important, it allows you to understand the world. Is it born or made? It’s more complicated than that: it depends on the person, if they learn how to read the images, to understand them. Sometimes young photographers come to my studio to ask me for advice, and I always say: “Study Image. I’m not sure if hand-crafted photography, the lab work I do, will exist in 20 or 30 years, but I do know that image will always exist.”

You declare that “a country without photography is a country without history.” Why?

Because I believe documentary photography tells the stories that have happened in a city or country. It’s necessary. The problem in Spain is that we’ve never had good photographic archives and that restricts a country’s memory. Throughout history, photography has been key because it allows us to understand situations. We understand the Vietnam war, for example, because a girl is running naked along a road after being severely burned by napalm. These situations can be explained with words, but an image conveys a different sensation.