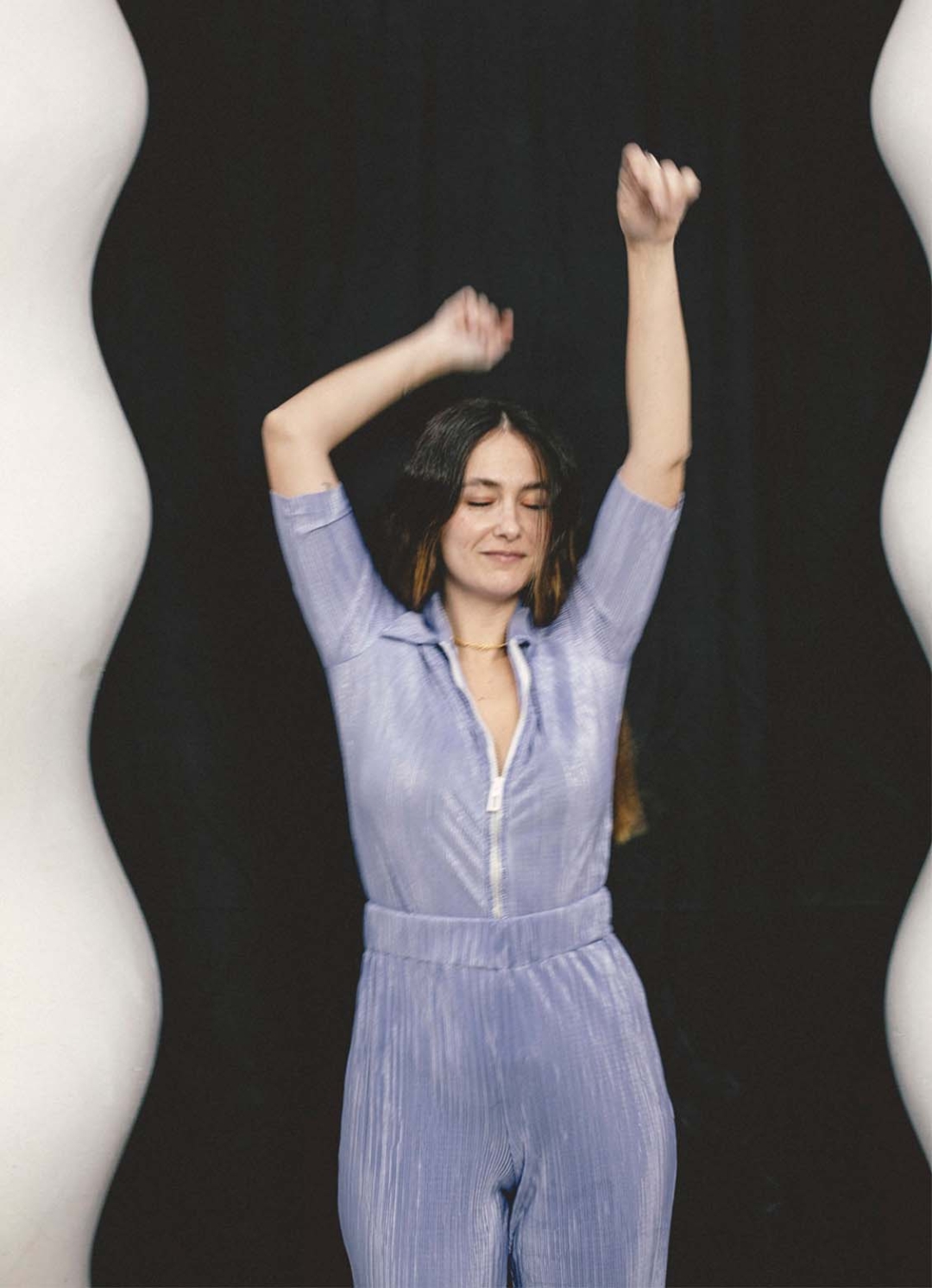

Lupe de la Vallina

With continuous light

Once, she told a friend: “What I want is to be discovered.” And that’s what happened. ‘Jot Down’ magazine saw her Flickr and distinguished a gaze. They were the first to perceive her and now she’s the one that can’t stop showing other gazes —those of her subjects— to the rest of the world.

The neighbourhood of Usera is burning and there are few brave enough to face the midsummer heat. When we step into the coworking space where Lupe de la Vallina (Madrid, 1983) has her studio, she still hasn’t arrived. Less than five minutes later, she appears. She’s wearing a long, flowing white shirt dress that seems to glow from within, like magic. We’re sure that, if Lupe herself had bumped into this image, she would’ve pulled her camera out to take a portrait. And talking about her relationship with her work tool, which has led her to publish for Jot Down, EL PAÍS Semanal, GQ, Marie Claire or Telva, we start our chat.

You have a camera in your hands, what happens next?

I start to watch what’s happening. Through the camera, you see everything differently to how you see it through your eyes. The other day I heard Alberto García-Alix say that the difference between looking through your eyes or through the camera is that, in the second case, there’s intentionality because you’re selective. With the camera you direct your attention and that of the audience towards where you want.

And does it have to be yours for the reaction to occur?

To be able to focus on a photo you need to not think at all about what you’re doing technically. So, yes, I need some time to get comfortable and for my fingers to move by themselves.

“The difference between looking through your eyes or through the camera is that, in the second case, there’s intentionality because you’re selective”

Tell us about your camera...

I bought it with my first proper salary, and I did it to go to Dominican Republic with a joint project between Jot Down and Intermón Oxfam. Until then, I felt really insecure because I had semi-professional equipment and every time I’d get more and more difficult commissions that were a stretch to do. Suddenly, I had the peace of mind of having invested in something real, that was true, and that would allow me to do things properly.

Who’d you say has power over whom?

It’s mutual. I’m the one who knows her and takes her places but obeying the conditions she establishes. Just like the dynamics between subject and photographer, neither can prevail over the other.

“I’m the one who takes my camera places, but, just like the dynamics between subject and photographer, neither can prevail over the other”

What awakened your talent? Have you always felt connected to photography?

To photos, yes. My father did his military service in the Sahara, and he made a bit of money capturing landscapes from a light aircraft and selling the photos to his comrades who sent them as postcards. When I was little, he gave me his Pentax, which was automatic, really manual, and I’d take it everywhere with me. Even so, it took me a long time to realise that it was a career choice.

Portrait is your genre in capital letters, which of the two meanings of the term do you like best: “a representation or impression of someone or something” or “combination of external and internal traits of a person”?

In both I’m missing the author’s intentionality. For me, portrait is an artist’s gaze of a person at a given time. I already learnt that I can’t bring out anybody’s essence. That’s not honest. A person is themself in a multitude of ways.

Your lens is really used to celebrities. Are they like ordinary folk or do they have a special talent for posing?

They’re photogenic gods. I give an actor, model, or dancer some instructions and they quickly understand what to do with their body. With actors, for example, I work with emotions directly. I give them roles. I asked Javier Rey to step into the shoes of a writer who was trying to finish his novel. Artists that are used to working with their image have a fine-tuned sensibility and know how to play with it fearlessly. If they’re sad, they use it; if they’re embarrassed, they use it. The rest of us are scared.

And can you capture and convey a person’s talent in a portrait?

You can capture intangible human qualities as long as you know how to perceive them.

“Artists are used to working with their image and know how to play with it fearlessly. The rest of us are scared”

For the Málaga Film Festival’s 25th anniversary, you starred in your first solo exhibition: 25 y seguimos de estreno. 80 portraits of Spanish actors. What did it mean to you?

I’m used to seeing my photos on the computer and in magazines, so seeing them on Calle Larios at one by two metres has been a dream. I fell in love with each person that posed in front of my camera, even though sometimes I only had a couple of minutes with each of them. On the first day, when I set up, my stomach got tied up in knots when I saw that the other stands all used flash photography, except me, who used continuous lighting. Did it matter? No, but in that moment, I felt impostor’s syndrome which made me think I was doing something wrong. My stomach settled after I took the first photograph, which came out great, and I forgot about it. I’ve grown ten years with this commission.

Annie Leibovitz, a photographer you admire, assures that her trick is to respect, relax, and wait for the subject, but maintaining emotional distance. Do you share her method?

I become their girlfriend! For 40 minutes, we’re a couple, and then “bye, nothing happened here”. To take photos of someone, they need to fascinate you and they have to let you do your thing. I don’t know how to achieve that without intimacy.

“To take photos of someone, they need to fascinate you and they have to let you do your thing. I don’t know how to achieve that without intimacy”

Who would you have liked to have photographed?

I cried when I found out about the death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman. I’d never thought about it and when it happened, I thought: there’s a world where I’m not going to be able to photograph him. I felt like I’d been robbed.

You’re a member of the Twitterati, is a picture worth 280 characters?

I always remember that images are a window that opens, and words, a window that closes. Tweets can narrate your inner conversation, showing you that it’s universal and making you feel united, but a good portrait will take you to depths that words can’t reach.