Paula Anta

Landscapes of resistance

Photographer Paula Anta presents ‘Paisajes de resistencia’ [Landscapes of resistance] as part of the official 2025 PHotoESPAÑA section. A journey to different places around the world—from Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal or Mauritania to India or the United States, without forgetting about Spain— that invites us to reflect on our impact on the environment. Until the 9th of June at the Torreón Fortea in Zaragoza.

“The most beautiful and most important thing that photography does is shine a light on people, events, or places.” Paula Anta (Madrid, 1977) knows this well. With her images, she has raised awareness about environmental disasters such as the toxic waste the Probo Koala tanker dumped in Côte d’Ivoire, for example. Nevertheless, her environmental message is never explicit because she aims to invite people to reflect calmly. This is why nature and artificiality are not confronted, but rather coexist, in her images. She defends that photography is a projection of each person’s way of being: “I look like a seemingly calm person, but in reality, I can’t sit still. The same happens with my photos, they convey peace and tranquillity, but getting there has often been hell (laughs).” Because Paula has photographed extremely complex situations, like the one surrounding her visit to the Mauritanian desert that she tells us about in this interview. These snaps, that belong to her Hendu series, are just some of the photos that are part of Paisajes de resistencia [Landscapes of resistance], her exhibition included in the official 2025 PHotoESPAÑA section —event sponsored by Iberia— hosted at the Torreón Fortea. In Zaragoza from the 8th of June. “It’s a journey through the landscape,” she explains. This exhibit also brings together other photos taken in India, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, the United States or Spain, of course. “One of my favourite things about taking landscape photos is that I’m alone, connecting with that place,” adds this seasoned traveller.

You studied Fine Arts and Piano, but photography has always been there, right?

I can’t remember a specific moment when I decided I would become a photographer. Really, it was a chain of events, which weren’t even related to photographic language, but rather to the creative process and artistic expression. I always enjoyed watching places transform, like the Parque del Retiro. My house was on one side and my high school on the other, so I would walk through it every day with my camera, taking photos of how it changed with the seasons. I also got caught in the chemical development process because, when I was studying, digital photography didn’t exist yet, and I was fascinated by lab work.

As an unwavering observer of nature, how much do we humans need to learn from it?

We come from nature. Mother nature, as the saying goes. A perception shared by all cultures on the planet. I think we’re connected to nature, although unfortunately, we feel increasingly cut off from her. As our mother, nature is a role model, and we must learn everything from her: survival, respect, coexistence… But we’re not on the right track. She is the one who feeds us, who protects us, and also punishes us.

“Finding more and more damaged natural spaces made me realize the need to raise awareness about taking care of our environment”

When did you realize that the relationship between nature and artificiality would become the main theme of your work?

I feel like the theme came to me after a lot of work, after many experiments and unsuccessful attempts. Also, from being free to take decisions and being unafraid. Undoubtedly, the theme has gradually been revealed because it connects with my gaze, my sensibility, my emotions… And it’s related to the present we have to live. As I was saying, I feel like I’ve been chosen by that theme as part of a learning process. It hasn’t been an intellectual decision, but rather the result of connections that may be invisible, but that are there and lead you to do what you do.

Even though you don’t like to impose a narrative, would you say that the ultimate purpose of your photography is to encourage a more respectful relationship with nature?

It’s hard to say which is the ultimate goal of my images… At the beginning there was no environmental narrative, even though I worked in a natural environment, or I could personally be an environmentalist, but I’ve visited places that have moved me to tears because of the brutal damage caused by human beings; landscapes of absolute beauty that have been completely devastated. That closeness to the natural world, finding more and more damaged natural spaces, gradually made me realize the need to raise awareness about taking care of our environment. If one of my images achieves this, even if it’s just with a single person, taking it will have made sense.

Can you introduce us to your Paisajes de resistencia exhibition?

The exhibition has been commissioned by Ana Berruguete, who has known my work for many years. In fact, she knows it better than me because she connected with it from the beginning. It includes a selection of six of my series in a unique venue, the Torreón Fortea in Zaragoza, which is a small Mudéjar-style medieval tower. Each room is a world because I introduce a very particular affected landscape. It’s also a kind of journey because we go from India to Senegal, through Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, or the United States, even reaching the grasslands of Extremadura.

You’ve photographed half the world. Is the journey itself a source of inspiration for you?

Absolutely. I always say that I’m not sure if I work as a photographer to be able to travel because it’s what I love the most. The journey opens you up to new experiences, other cultures, other points of view… It’s like a reset. “Move away as far as you can from where you come from and open yourself to everything you are going to find,” I tell myself. Always respectfully. When you interact with people from other cultures, things become relative and those you thought were fixed are no longer set in stone. In short, for me, the journey is inspiring because it makes you less important and opens you up to something much larger, the world.

“For me, the journey is inspiring because it makes you less important and opens you up to something much larger, the world”

Your photos convey serenity, calmness, stillness… Do you feel these sensations when you take them?

Yes, my photos convey that… In fact, two years ago, I did an exhibition at the Galería Daniel Cuevas called Jaam rek, which means “in peace” in Wolof, a language spoken in Senegal. And that was because the selected images conveyed precisely that. But how I take them is a different story. The best example is a series [Hendu] I took in the desert of Mauritania. It was quite a dangerous area because ISIS was patrolling it, there were landmines, and we had to go through military checkpoints. This work was not surrounded by calmness, but the images do reflect the peace and poetry of the landscape, even though there was underlying criticism.

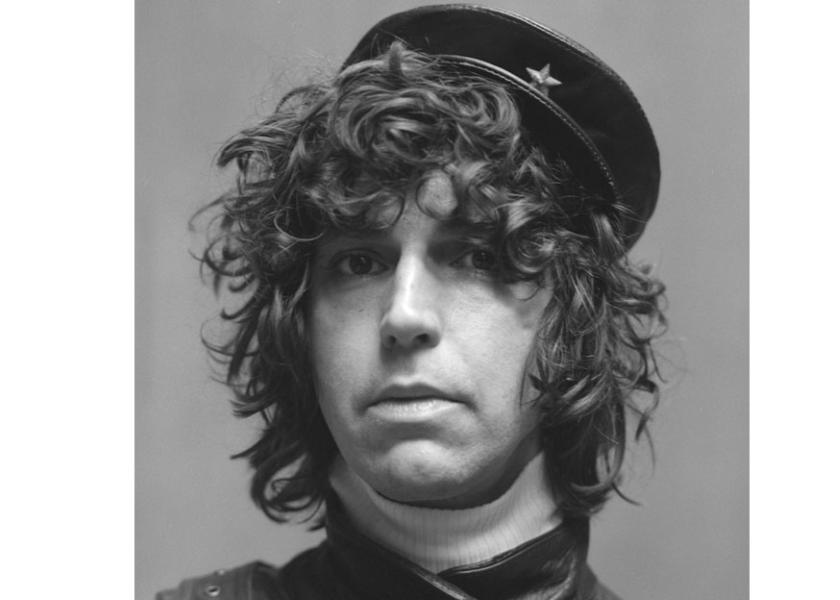

You started to play with portraits to help you overcome your shyness. Did it work?

Not really… (laughs). I was also attracted to the artificiality of portraits, as well as their connection to paintings. The way I build my images is almost more connected to a painter’s process than to that of a photographer. In the case of my portraits, there’s a close relationship with Baroque painting. When I photograph people, shyness fades into the background, but then it comes back. If you’re shy, you’re shy, but portraits are a good psychological exercise and it’s a learning experience.

You also teach, so you know up-and-coming photographers well. How talented are the new generations?

I like to promote young talent because they don’t have it easy and there are some incredible people. I feel moved by their energy. They need us to bear them in mind and keep them in the loop because they’re not lacking talent, they are people who are making quite an impression and have a lot to say. In the end, this is like a circle, and I also learn from them. They are well-prepared, even though they have access to a lot of information, and sometimes they struggle to cull it to find their own language.