Jorge Fuembuena

The favourite game

Curiosity, intuition, empathy, complicity, intimacy, and commitment are the driving force behind Jorge Fuembuena’s photography work. Intricately connected to the world of film, he’s one of the leading still photographers for film shooting in Spain, he has taken portraits of film stars like Ryan Gosling or Jessica Chastain, and has also thrown himself into projects dedicated to Buñuel, Pasolini or Berlanga.

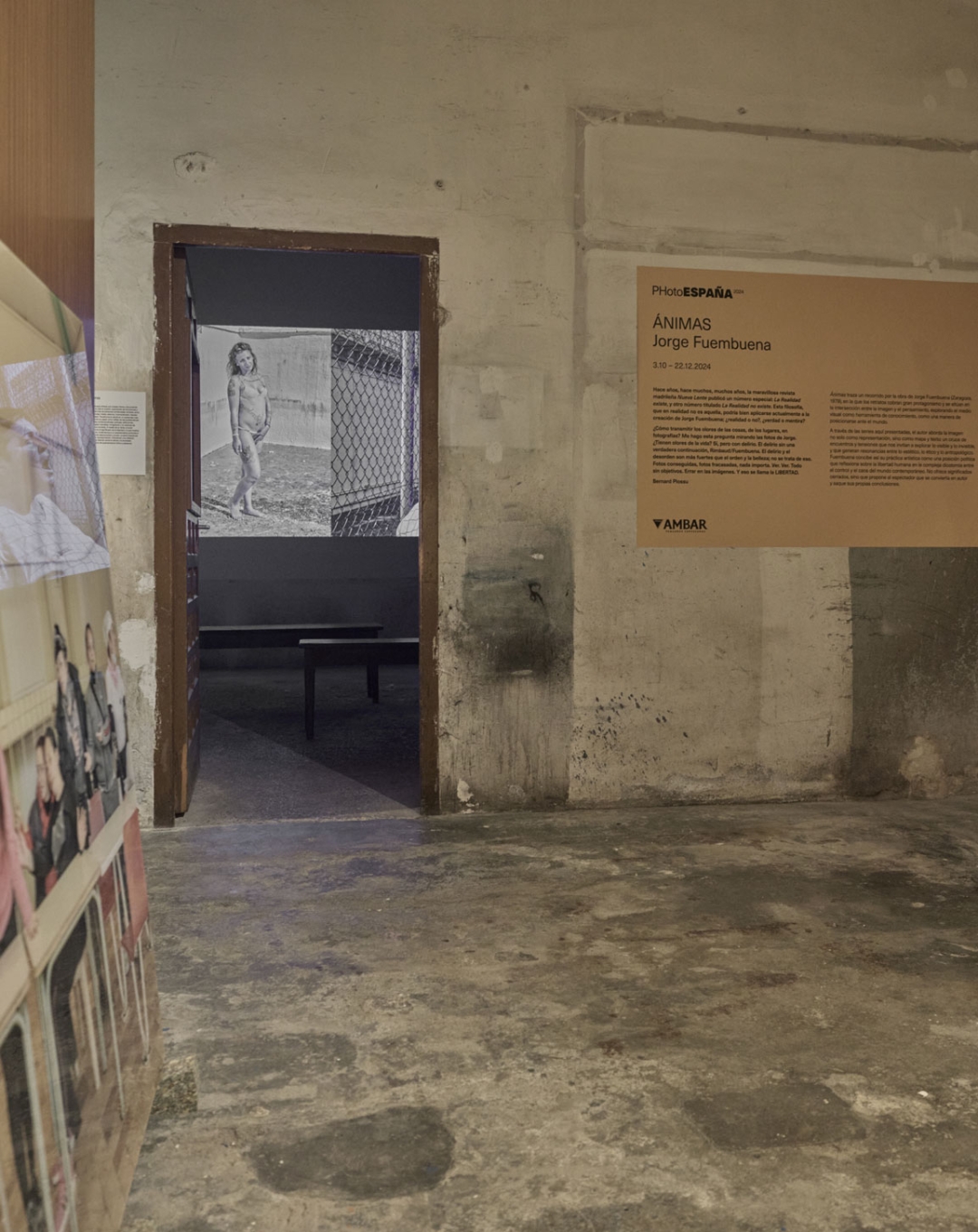

“A portrait is an invitation to play.” Jorge Fuembuena (Zaragoza, 1979), a photographer for whom “there’s no shot, but rather action”, has allowed himself to play with big film stars, looking them in the eye and turning knowing silence into his best ally. The result is a hypnotic series of portraits —taken at the San Sebastián Film Festival, where he’s been the official photographer for years— featuring Kristen Stewart, Timothée Chalamet, or Susan Sarandon, among many others. It’s no coincidence that this photographer from Zaragoza uses the term “play”, because the act of taking photographs connects him to his past: “I take photographs as an act of love, it allows me to connect with my childhood, with innocence, it takes me back to myself as a boy.” When we ask him about talent, Jorge recalls the validity of a virtue that many lose over time: “The basis of everything is a constant longing for curiosity. The act of creating is illogical and we have to forget about logic. Intuitive experience is what pushes us into an image.” Whoever wants to step into his can visit Ánimas —until the 22nd of December at La Zaragozana (Fábrica de Cervezas Ambar)—, an exhibition that’s part of the Official Section of PHotoESPAÑA that suggests “an infinite journey through my visual universe”, through photos that are “sounding boards” ready to be observed, but also listened to.

Photography is your life but, how did your relationship with it come about?

It comes from my travels around the world and from curiosity. I’m receptive to most things, but I always have a slightly sceptical perspective; you have to discern what’s behind appearances. Photography precisely deals with this indescribable, unexplainable thing, and there are few things as eloquent as the silence of photography. Taking photos has a secret voice.

And what is Jorge Fuembuena’s voice like?

An educated gaze, which expresses itself about the world from an incomplete, fragmented, or immediate perspective. Space begins because we look beyond where we are, beyond ourselves. There’s a vision based on silence and on how the documentary perspective creates a position regarding the world. Photography isn’t about explaining, it’s about evoking and suggesting. The key is working between what’s visible and invisible, building bridges between them.

“Photography isn’t about explaining, it’s about evoking and suggesting. The key is working between what’s visible and invisible, building bridges between them”

What can you tell us about Ánimas, your current exhibition at PHotoESPAÑA?

The exhibit explores the portrait genre. The structure of the exhibition is such that the different series are interwoven through a route with secret links that build an infinite journey through my visual universe. It’s like a rhizome, establishing tensions, dialogues, overlaps, echoes, or resonances between images. It’s confrontation and coexistence. This installation is a specifically designed construction in terms of the editing and choice of formats, for those old studios. The works coexist and are in conversation with such a symbolic space.

Your work is intricately connected to the world of cinema. Has it been your biggest inspiration?

I do still photography for film. I build exhibitions and publications with filming images. I also work as an official photographer at different film festivals, like in San Sebastián, Málaga, Nantes... As an author, I’m interested in the intersection between cinema and photography. I’ve spent the last 12 years working on the Luis Buñuel universe. Basically, on three concepts: faith, eroticism, and death. The work connects archive and found images with fabricated images and simulations. I’m also working with Luis García Berlanga’s erotic library. These are 20,000 annual subscription magazines that belong to the film director which allow us to reflect on our relationship with desire, the body and gender.

Your talent has transcended borders. Tell us about your Pasolini project.

It’s named after one of his novels, Raggazi di vita (1955), and follows the experimental line of intersectional projects between cinema and photography. I started during a grant at the Spanish Royal Academy in Rome. I explore the beauty of failure in the borgate kids, the youth that wander the streets fending for themselves. Their gestures and body postures recreate some of the paintings by another cursed artist, Caravaggio. The streets on the outskirts of Rome are the scene of resistance where a community is built, and the place that enables me to take a stance in a clear exercise of political activism. During the research phase, the film director Gaspar Noé and I shared documentation, ideas, and concepts. With his films, Pasolini broke the aesthetic traditions of that time, like Buñuel did with The Young and the Damned. I presented this work at PHotoESPAÑA and people could visit it at MAXXI, the national museum of contemporary art in Rome.

“The soul of photography is portrait. In my portraits, there’s an intimate distance with the subject, who looks back at you, captivates you, and questions you”

Last summer, your portraits of film stars presided over the Galería de Cristal at the Cibeles Palace in Madrid, during the Cibeles de Cine cycle. What are these types of gatherings like?

The soul of photography is portrait. In my portraits, there’s an intimate distance with the subject, who looks back at you, captivates you, and questions you. A portrait is a mystery without a permanent resolution, an instrument to meet another. I get rid of anecdotal or accessory material. The prestigious Mk2 commissioned the exhibition, courtesy of the San Sebastián Film Festival, where I took those portraits as the official photographer.

As a photographer, in which context do you feel most comfortable? In front of a film star or an anonymous person?

I’m not interested in complacent portraits, but rather complicit ones. That pact, the chemistry and connection in that space with the subjects is direct, we’re on the same energy wavelength. I try to make people feel at ease, they are giving me a part of their life —their time and trust— and you must be grateful. It’s a gift. I’m very delicate and tender, and I speak to people with conviction in what I do. I’m interested in more psychological portraits, where the gaze is the key element, where an emotional space is built. I’m always looking for emotional connections, a levelness with people that’s determined by the gaze of the subject that I’m taking a portrait of.

Is there a line separating the photographer from the artist for you?

Ideally, there’s an overlap between personal and professional work, that they are going in the same semantic direction, both from the freedom of creation. My film work feeds my work as an artist, like Richard Avedon did in his day. The fact that my passion coincides with my profession is a dream.

“Photography is an act of faith, and I like to convey enthusiasm and promote growth, as a person and as an author”

You’re also a teacher. What do you like to convey to your students?

For example, I tell them: “If this image were music, what genre would it be? How many and what kind of instruments are there? It’s a statement, through a gaze and ideas in order to share questions and stimulate critical thought. Photography is an act of faith, and I like to convey enthusiasm and promote growth, as a person and as an author. I give lectures and conferences at photography gatherings and festivals, as well as workshops at different photography schools.

And who have your masters been?

The first who taught me how to look was Bernard Plossu, who writes the text in Ánimas, a living legend in the history of independent photography with whom I did several hikes in Sierra de Guara (Huesca) more than two decades ago. My learning is also indebted to authors such as Alberto García-Alix or Miguel Trillo; we play at taking portraits of ourselves. In turn, I’ve learnt working with film directors like Carlos Saura, with whom I had a great friendship and who wrote a text as a personal letter for my book ELEGIES, published by RM.