Almudena Romero

The developing power of plants

Almudena Romero cultivates and develops images through plants and sprouted seeds to defend the importance of sustainable and fleeting photography. 'Sensitive' petals and leaves capable of conveying a new concept of time and nature.

It’s midday on a Friday at a country house in Valencia, where the bumblebees fly over plants turned into works of art. Nobody would imagine that the lab of multi-award-winning visual artist Almudena Romero (Madrid, 1986), artist in residency at the National Portrait Gallery in London and professor of photography at Stanford University in Florence, could be hidden in her grandmother’s garden, on the Mediterranean coast.

Among the bougainvillea and oleanders, she puts into practice the knowledge passed down from generation to generation to understand nature’s timings, solar cycles, and their impact on plants. In this garden, she cultivates and experiments with leaves as part of her research project, The Pigment Change, which, after visiting the Rencontres d’Arles, will be exhibited at the international Paris Photo fair. Considered one of the pioneers in 21st-century 'biophotography', this specialist in 19th-century developing techniques has been able to combine art and environment through photo printing.

After studying ancient photography techniques for years, what sparked your interest in photosynthesis and plants as a creative medium?

I used to work a lot with the collodion wet plate process, the technique that allowed the first negatives on glass, which, in turn, made the first copies possible. This technology had an enormous impact on how people saw themselves and how they wanted to edit themselves for others. As a specialist in 19th century techniques, I had read the treatises by John Herschel, inventor of blueprinting and the idea of “writing with light”, and his correspondence with Mary Somerville, who actually collaborated on this research on photography, but couldn’t publish it under her own name because she was a woman. And this led me to think about the impact of photography on how we understand ourselves and our expression within the world.

Which was the purpose of that photography and how is it different from contemporary photography?

Herschel and Somerville were looking for colour printing and discovered sodium thiosulfate to develop images. This was revolutionary. But, at the same time, the chemistry they worked with, the collodion wet plate process, has a significant environmental impact, like all analogue photography. I knew that the purpose of that photography in the 19th century was exploitation, production, and commercialisation. But we have overcome that today, we have a real climate crisis, and this led me to reconsider how to print more sustainably, changing our relationship with nature. Thus, The Pigment Change project was born.

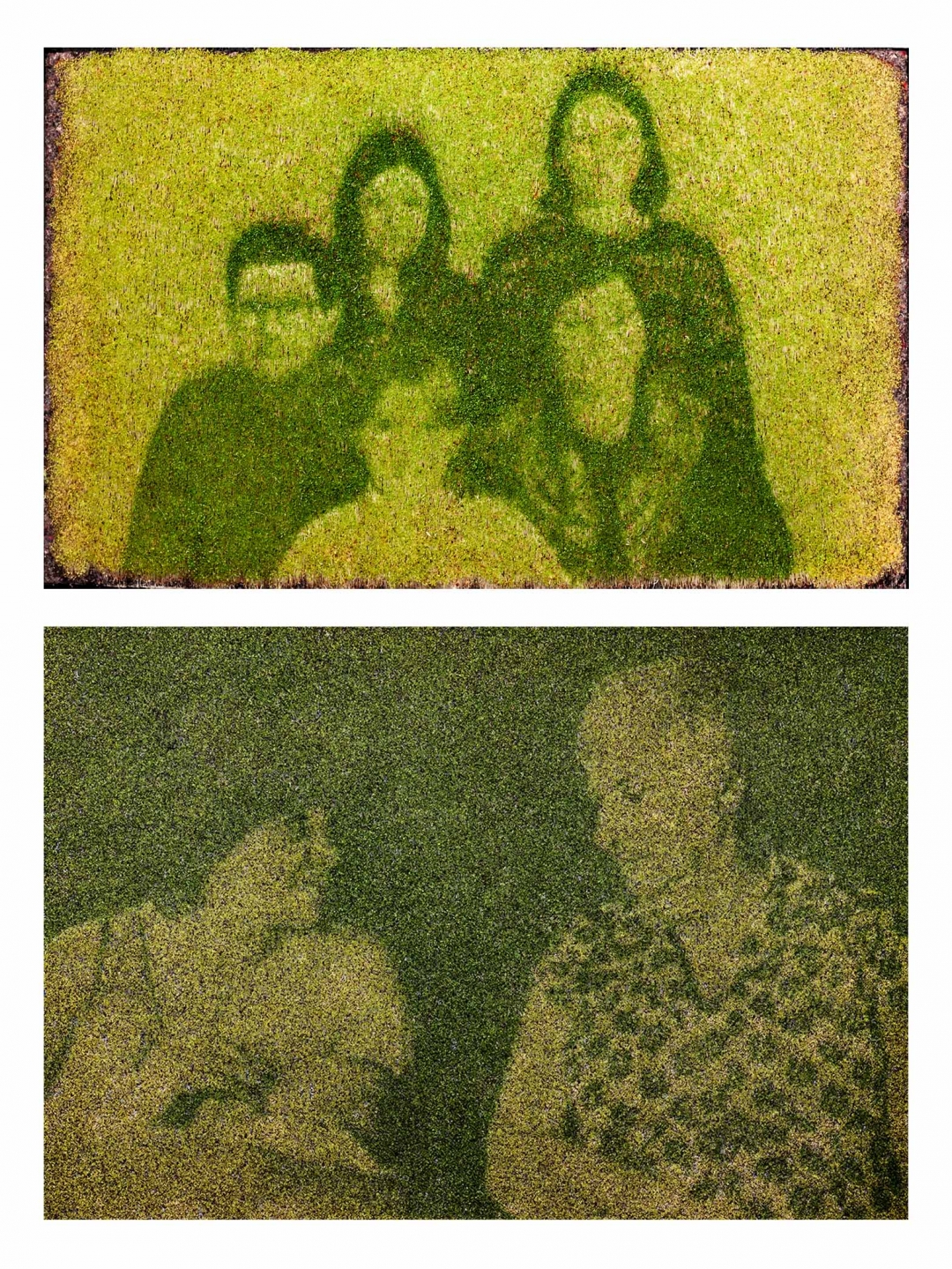

The artist’s work invites us to reflect on the fleeting nature of things and on legacy. Images from her project 'The Pigment Change - Family Album'. © Almudena Romero

Do you believe that your photography could be a source of inspiration to defend the environment?

I believe it’s useful for understanding nature from a different perspective. My grandparents were farmers, and my grandmother taught me a lot about observing: how to plant, cultivate and take care of plants. This leads to an introspective exercise, to a different conception of time: “To develop certain images I need this type of leaves and they’ll need exposure to the sun for so many days”. Then it clouds over, and you have to wait. Or the seeds follow their process and deteriorate, like printing on watercress. You have to get used to the idea that temporary things can be the most sustainable, especially when it seems like they’re not worth it anymore. We have to change the discourse. This is a relevant problem and I believe that artists and researchers should promote it and send a message to the art market: “My work is temporary”. It’s important for the market to adapt to the artist, and not the other way around. The idea of producing for production’s sake is at the heart of the environmental crisis.

“You have to get used to the idea that temporary things can be the most sustainable, especially when it seems like they’re not worth it anymore”

Your project, The Pigment Change, prints images on plants. What’s your creative process like?

In the first chapter of the work, I ask myself two questions: “Do we really need to produce? Which is the role of artists in this environmental crisis?”. From there, I develop images of hands, as a symbol of production, on leaves that are preserved in bioresin. I observed that the plants that are facing north in my grandmother’s garden are the ones that take on the image better, because they’re not used to the sun. Chemically, there is a pigment change, as a survival mechanism, and that is what I use.

And how does that mechanism work?

Plants “break up” their chlorophyll and generate carotenes as a reaction to excess energy, to excess light. So that the sun does not interrupt the natural photosynthesis process, carotenes let the light through so that they don’t “burn”, so to speak. I look for plants that allow this pigment change and, on top of them, I place an acetate sheet where I’ve printed the image I’m looking for, and I expose them to the sun to make the most of that chlorophyll breakdown. Once the leaves have been printed, I submerge them in a 1% diluted copper bath so that the pigment becomes much more resistant to the amount of light in a gallery, for example.

When you were awarded the BMW 2020 Photography Residency with this project, did you face resistance due to the possibility that your final work may self-destruct?

Quite the opposite, they were very aware of this, and I received all kinds of help. The residency includes two programmed exhibitions, but they accepted that there was no produced work, so we decided to document the creation process. They knew from the beginning that I depend on the plants’ reaction and that there was a possibility that it wouldn’t work. After trying all kinds of mosses and leaves, it’s taken me eight months to find the watercress seed as a medium for the Family Album block, where I cast old family negatives. I enjoy printing on sprouted watercress because of the grain achieved, its grey scale and definition. But they only last around five days and then they rot. We’ll see if they’ll last for the exhibition days at Paris Photo.

“It’s important for the market to adapt to the artist, and not the other way around. The idea of producing for production’s sake is at the heart of the environmental crisis”

Your work not only entails the effort of getting the plants to develop the image, but you’ve also broken the artistic secret taboo. Why?

As an artist, you have to think about how and why you produce. Is it just a problem of the ego, does it bring anything to the conversation? Showing my creative process, overcoming difficulties, is important to me because I believe that knowledge is universal. Who benefits from the secret techniques of a “magical artist”? The art market, the elites. I don’t fully support that exclusivity. That’s why I disclose my process through my media channels, so that anyone can try this technique at home. I’ve had teachers see my videos on YouTube and then teach the technique to their students. It doesn’t matter that the students aren’t aware that I was the one who put in the work of experimenting until achieving the result: for them it’ll still be an enriching experience.

Why this deliberate search for fleeting art? Wasn’t the purpose of photography to make us immortal?

It’s true, the purpose of old family photos was to tell the story of who we are; the concept of “legacy” is integral to them. But which legacy do we want to leave future generations? I believe it’s not only about thinking about who we were, but what we’re leaving behind. This is also closely related to what children will need. I’m more interested in “what” than “who”. And I don’t know how we’re going to live in the future. I’m not sure if access to water will be guaranteed, for example. In my opinion, the role of artists is to contribute to reconsidering ourselves, that’s why I want to reflect on the fleeting nature of things and on legacy. Beyond producing art pieces that become part of large collections, I think our purpose is to shift the way we think. A new conception of ourselves and nature.

“It’s about shifting the way we think. A new conception of ourselves and nature”

Does your research prove that plants are able to take photos?

This is what the last chapter, Faire une Photographie, is about, where I study the poinsettia’s colour change: I place it in a black box and modify the light it receives to make it change from green to red. I believe that, if there was no light pollution in cities, the plant would change colour by itself, given enough contrast between light and darkness. But if the plant can perform the photographic process by itself, who takes the photo, the plant or me? Can plants also make art? This question led me to a second part of the project, which I’m already researching.

What will this upcoming work consist of, and which technique will you apply?

Now I’m reading Stefano Mancuso, an expert in plant neurobiology with an interesting theory that plants “play”. That they are smart, they can think and act accordingly. For example, flowers have a system that makes “marks” on their petals, which can only be seen under ultraviolet light and help guide and attract pollinating insects. I’m researching both aspects: whether plants can make art by themselves, on the one hand, and on the other, how the idea of guiding pollinators works. Maybe they’re just playing? To show these ultraviolet marks, I need to use digital technology. Where does this lead us? It’s important to do photography with the least environmental impact possible, it’s true, but if achieving zero impact prevents me from writing the discourse, it’s no use. The goal is to move towards a different awareness about nature and to use the most sustainable technology possible.