Rafael Fabrés

The Visual Storyteller

A photographer and a reporter at the same time, Rafael Fabrés is finalising his book 'Cafuné', a heart-breaking work that documents the pacification years of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and describes a hard and complex city during some key years for the future of the country. “I’m at a stage,” he says, “where I’m more interested in telling a story than in photography itself.”

Just in from Kathmandu, we have a chat with Rafael Fabrés (Madrid, 1982), who, right from the start of our conversation, insists (“do please phrase it like this”) in describing himself as a “photo documentary maker” and not as a photojournalist. Which, on the other hand, his work seems to contradict since he publishes in international media outlets such as The New York Times, Time Magazine, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, The Guardian, El País, and Paris Match, among others. His images of Haiti devastated by cholera, terrorist attacks in Afghanistan, the pacification process of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, or the last great earthquake in Mexico have been seen by people all over the world. But despite being a contemporary of and sometimes working in the same places as colleagues like Manu Brabo, Guillem Valle, Samuel Aranda, and others whom Gervasio Sánchez considers “the best generation of Spanish photojournalists”, Fabrés says he feels “not a part of that group, although I’ve also treated subjects that can be considered tough.”

His real start in the profession — “a proper learning experience”— took place in Haiti, after the earthquake and the subsequent cholera epidemic of 2010. His stay in Port-au-Prince was extended from one month to two years, until “the international media, as usually happens, unfortunately, changed their focus from Haiti to the start of the so-called Arab Spring in Tunis.” So why Brazil and not the Middle East? “I considered going to Yemen or Libya, but I read about the pacification process in Rio de Janeiro, and I felt there was a story to tell.” Six years before the Olympic Games and other macro events in the capital of Rio, from the World Cup to the Pope’s visit, the city’s transformation had just begun.

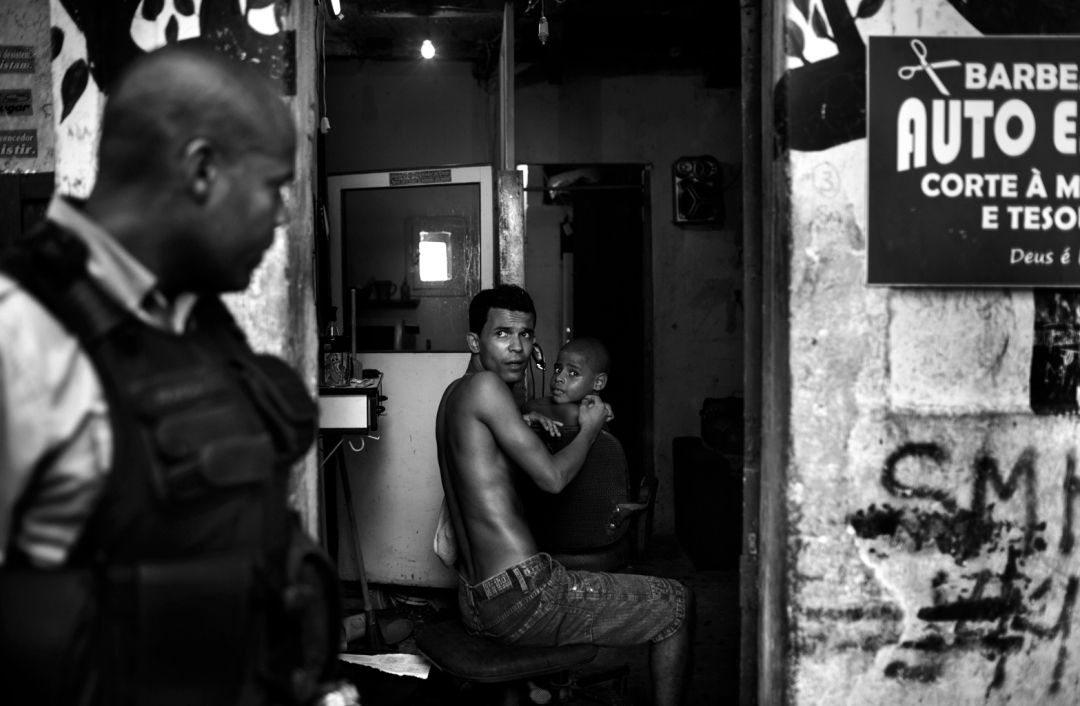

Interestingly, of the thousands of photographs Rafael Fabrés took during his time in Brazil, none are taken during sports events. The story was there, in the more complex communities where the pacification didn’t work. “Those areas were far removed from what was shown to the press, whose access was restricted to the favelas they call bonitinhas, located in the noble areas of the city, where the process had been much simpler,” he explains. His embedment with the Pacification Police Units and their interventions in the most conflictive morros (hills), such as San Carlos, were the basis of images published in many media outlets and as part of the Pacification project, presented at the Visa pour l’image festival. They are tough, violent photographs of night patrols in the shantytowns of Rio, and they were also the beginning of the end of Rafael Fabrés’ stay in Brazil, after more than five years.

Youngsters enjoy in a football arena in Complexo da Penha, Rio de Janeiro. © Rafael Fabrés

“This job, regardless of who or where you are, involves a series of problems such as feelings of uprooting, sacrifice, uncertainty and instability,” he says. “I wasn’t tired of the pacification as a project, but of the violence. I couldn’t see myself going on with a story that I no longer felt was mine—I could no longer see a way to tell it from a personal perspective to move forward with it after seven years.” This led to a change of scenery; he travelled to Mexico City and to India, among other parts of the world, where he went back to developing more personal projects and collaborations with NGOs, involving subjects and stories away from that violence. “At a creative level it’s important to me to always be on the move. It’s what makes me discover the topics that are interesting on a visual level, which is difficult to do if I stand still,” he says.

The distance and spending two years in Mexico allowed for, above all, a change of focus: “I began to see the potential of my work in Brazil; not only Pacification, but everything—photos, texts, poems, drawings—that has emotional weight. Suddenly, Pacification disappeared, and the idea started to form of developing a book with all that content, the stories that have the pacification process as a backdrop.”

Photography as therapy and images that ‘work’

Right now, things have quieted down, so to speak, for Rafael Fabrés; currently based between Barcelona and Madrid, he’s still on the move with projects in Mexico, Spain or Nepal, while finishing the final details of his new book. Cafuné—Brazilian Portuguese for the act of caressing or tenderly running fingers through a loved one’s hair—narrates an episode that’s been key to the future of the city and the country. “Often, our job is to try to adapt to a reality you don’t know the workings of from a perspective that’s focused very much on the harshest and most violent environment. That’s why Cafuné also tries to take stock and look at the impact all this has had, on my life, on the one hand, but most of all, on the city.”

After subjects like pacification, US medical units in Afghanistan or the rescue of Chilean miners from Copiapó, to name a few examples, this episode may seem calm and even simple for those who follow Rafael Fabrés’ social media sites on a daily basis. “No, no [laughs]. The things I photograph when I am back here in Spain are usually more personal subjects, a visual exercise about my family, about that uprooting we talked about before, and everything that entails having lived away from home for so many years and coming back; the shocks and contrasts of that outside reality and the one on the inside. It’s important to me, because it’s almost an exercise in ‘photo therapy’, if you will. In this case, photography gives me a certain sense of identity, belonging, sense, flow. I don’t really know how to explain it.”

“Taking a good picture is very complicated and requires not only talent, but also intensive preparation, both mentally and technically”

Have you become a better photographer over the years? “Yes and no. Perhaps it’s easier now to solve certain issues—especially when using a tool like a camera—in the construction of an image that works; maybe that’s become more of an instinctive thing than when I started,” he says. “Taking a good picture is a whole different story; it’s something very complicated and requires not only talent, but most all intensive preparation, both mentally and technically. Photography is an activity in which there is always a high percentage of factors that are very difficult to control, so to speak. Talent is important, but the key is work, perseverance and constancy.”