Gervasio Sánchez

“In Photography, Every Day You Learn Something Different, Every Day You Start Anew”

We all see, but few of us really look. Fortunately, there are special people that force us to stop and pay attention to the world around us, artists that lend us their eyes to rock our consciences and help us see reality through a new filter. Gervasio Sánchez, one of the most internationally-renowned Spanish photojournalists, is a good example.

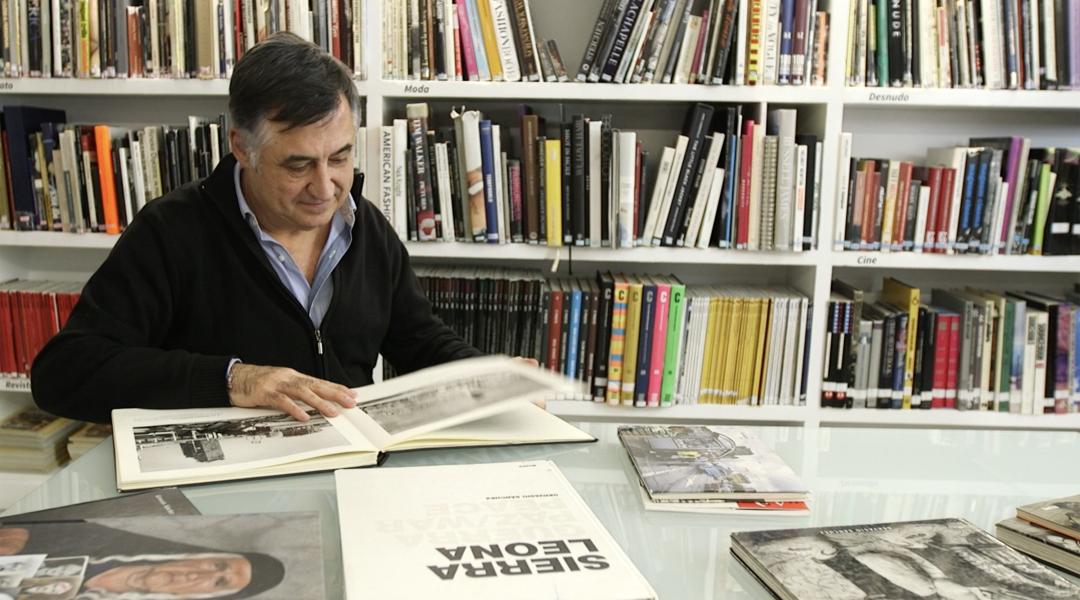

Gervasio Sánchez (Córdoba, 1959) is a pure-bred photojournalist standing on three solid pillars—professionalism, commitment, and honest work. He has won several awards, including the 2014 Bartolomé Ros PHotoESPAÑA Award, the Ortega y Gasset Award, the King of Spain Journalism Award – twice – and the 2009 National Photography Award. We meet Gervasio, a UNESCO Special Envoy for Peace since 1998, in the library of the Centro Internacional de Fotografía y Cine (EFTI – International Centre for Photography and Film), where he teaches and to which he feels specially close. “I’ve never taken a photography course,” he says. “Everything I know I learned it on the fly. Every day you learn something new, every day you start anew.”

Who were your models at the beginning of your career?

In Latin America in the early 1980s I met the world’s best photographers, both new and consecrated. We used to meet during trips and at lectures. On 25 November 1986, I met an Italian photographer in Chile, Ivo Saglietti, who worked for Newsweek, Der Spiegel and Stern. He was 10 years my senior and he taught me how to get on in certain situations. Watching other photographers work helped me develop my own style.

How do you find talent in a young photographer?

Sometimes you find young talented photographers who have missed opportunities or who become defensive in the face of criticism. That’s why I’m against giving awards to under 30s. I believe they should be encouraged with scholarships so they can submit better projects. I also see young people eager to learn who do it with effort and a critical attitude. Genius and geniuses don’t exist—what we have is people working hard every day.

What has more weight in a good photograph, history or technique?

Technique is important, but if you don’t have a good idea and you don’t develop it well with a personal narrative, you won’t get anything. The best way to become a good photographer is to copy others, being careful the copy isn’t too close to the original.

Why do you continue photographing the victims featured in old series such as Mined Lives or The Disappeared decades later?

When you see such brutality among humans, you need to balance out your emotions with different stories. Following them for months, years, or decades help me improve my mental health and find the strength to believe that all is not lost. Over the years, I’ve realized that, when everything falls apart, the worst of humans emerge—we are coward and violent, and we prefer to kill rather than die. Thanks to these long stories, I’ve improved as a human being and I’ve never thrown in the towel.

Do you still have hope despite what you’ve seen and photographed?

I know many stories that happened amidst the chaos of war and violence that make you think all is not lost. In December 1992, in Sarajevo, I interviewed a woman who had been raped by Serbian soldiers. However, she was grateful that her 14-year-old daughter hadn’t gone through the same because a neighbour had hid her out in her own home. The problem is that these people, anonymous heroes, are never rewarded and are always forgotten. When you hear the story of someone who has prevented someone from being raped you feel better about yourself.

How is the worst of the human photographed?

You’re there, in the middle of that disaster and wonder—what have we become? It’s very common to see people trying to exonerate themselves despite being guilty. Because guilty aren’t only those who kill—you’re guilty for acts of commission but also for acts of omission. There are passive offenders, people who turn a blind eye, people who point others and people who feel no empathy for the victims. It’s hard to find innocent people in a context of war.

What is photography for Gervasio Sánchez?

It can be art, a trade, a way to understand or document the world. It’s a very valuable educational weapon because children learn to read images before they read words, so photography can serve as an impressive educational manual to better understand the contemporary world. The adage “an image is worth a thousand words” is not true, but if you build a proper story photographically speaking no text can refute it. I’ve known this for many years. Being a photographer allows you to go further than if you only use a literary language.

Do you consider yourself a good photographer?

I’ve never taken a photography course... I’m a career journalist, but not even in the five years I spent at the Autonomous University of Barcelona I took a photography class. Everything I know, which isn’t a lot, really, I learned it on the fly. I watched the world’s best photographers work, I would stop shooting to see them, to ask them for advice, to understand their criticism as a source of wealth for my own way of seeing, which was also self-critical. In this profession every day you learn something different, every day you start anew. If we don’t do a better job after becoming consecrated, if we lose quality, everyone will realize, and that may bury us.