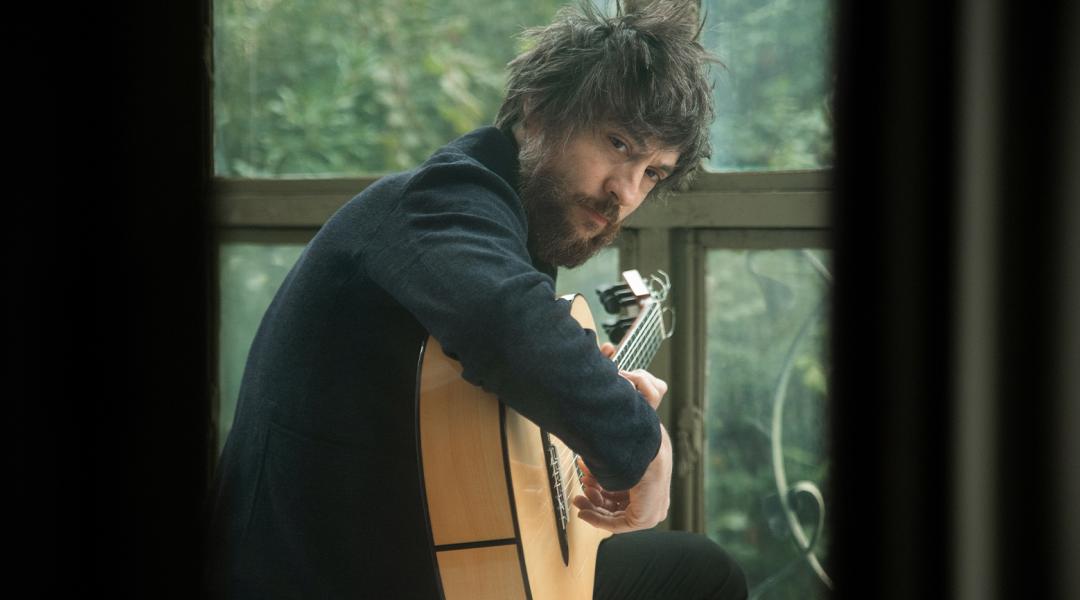

Raül Refree

At the Roots

In the last few years, Raül Refree has become one of the most important and international producers in the Spanish music scene. His name is linked to the new flamenco cultivated by Silvia Pérez Cruz, Rocío Márquez or Rosalía, but is also connected to records by Mala Rodríguez, Albert Pla, Josele Santiago, Kiko Veneno, and now also Rodrigo Cuevas’ awaited new album.

Raül Fernández Miró (Barcelona, 1976) knew that he wanted to make music from a young age. Not because he played the piano at his family home, it was simply a matter of depth, an expression that the musician continues to use to try to explain his work. He fulfilled his dream of making a record in the mid-90s with the hardcore group Corn Flakes, but he didn’t settle for that. ‘Evolution’ has been the keyword in his career and, today, his stage name Raül Refree, is a guarantee of creativity, quality and risk. As Refree he has recorded nine solo albums, where he combines folk, rock and experimental music.

What was the experience of working with Rodrigo Cuevas on Manual de cortejo like?

It’s been delightful, I’ve had a great time. Producing for him was a personal goal, I love what he does and his personality. I was also attracted to the idea of recovering traditional songs from the north of the Iberian Peninsula and giving them a more contemporary feel.

The record belongs to Rodrigo but you’ve both signed it. Has it been more of a collaboration than a production?

Rodrigo felt that we were both making the record. We drove to Asturias for me to experience the songs by women from Asturian villages, to learn from them. We recorded them, documented them and learnt the songs that we wanted on the record. They taught me music that was unknown to me.

It’s unusual for the producer to become a sort of collaborator.

This is something that is happening to me lately. I went to New York to work on Lee Ranaldo’s new record, Names of End North Women (on sale in February) and there was a moment where he said to me: “Wait a minute, Raúl, this is a duet album, you’re writing, it belongs to both of us”. I think this is because I understand the role of producer as someone who is by the artist’s side from the beginning, when they start working on the songs when they’re in the womb. I enjoy thinking about sound, arrangements, mixing. I get very involved, it’s the way I work.

You’ve crossed paths with traditional music again. Before it was flamenco, now, with Cuevas, Asturian folklore.

I feel lucky because interesting people always come looking for me, people who I can work with but also learn from. Over the years, I’ve realised that I’m really interested in grassroots music. I feel strong emotions when I reread traditional songs. The fact that this music has been passed down from generation to generation makes it extremely strong, and working with such powerful material allows you to dress it in different ways. At this time of complete globalisation, where information travels at the speed of light, local music acquires a lot of strength and can be more contemporary than other current music I listen to and that is considered avant-garde.

“I’m really interested in grassroots music. I feel strong emotions when I reread traditional songs”

You worked with Rosalía on her first album, Los Ángeles. Could you give us an example with her?

Rosalía is the perfect example of the fact that local roots can have a universal scope in the hands of someone talented and, at the same time, with a perspective that is very much of her generation. Rosalía can’t help being anything other than herself. She’s managed the traits that make up her personality very well. When she’s criticised for making reggaeton, that’s also a part of her, she’s both things, she’s not fooling anyone. For an American, listening to flamenco like Rosalía’s is much more interesting than listening to conventional rock or pop, which often sounds the same as other songs.

Do you believe that what she’s doing now is in tune with the record you produced together then?

I think that Rosalía already had a clear idea about what she’s doing now before I started working with her. We met, we started playing together, we liked what we made and wanted to make a record together which, more than a progression in her career, was a break from what it was meant to be.

Raül Refree during a break at his studio. © César Segarra

In your role as a solo artist, you have experimental records like La otra mitad or Nova creu alta, which are difficult to fit into a single genre.

Over the last few years, I’ve worked on records to do with flamenco that purists didn’t like much, such as Rosalía, Rocío Márquez or Niño de Elche. When I have the chance to talk about it, I tell purists that for a genre to survive the passage of time, it must have two things: people interested in preserving it and other people who keep it moving and work on making the more experimental part of the style survive. Musical frontiers are ridiculous. When you listen to music from the south of Spain all the way to France, there is a gradient there and not a jump; Occitan music has a lot to do with music from the north of Spain. This is how I think about it in my creative life, there’s no hard line between what I like and what I don’t like. For me, music is something that is very deep.

Which purists are fiercer, those who love rock or flamenco?

I started hearing flamenco purists when I produced Rocío Márquez’s first record. She told me: “Yikes, they’re going to have a go at me...”. I thought that she was exaggerating, but then I realised that she wasn’t. They said some odd, strong words to her. And this has happened again with Niño de Elche’s record Antología flamenca or Rosalía’s Los Ángeles, where part of them didn’t like it because they didn’t consider it flamenco. I saw some very nasty comments. Now I’ve made a Fado record, and I guess there’s always that risk. This is always going to happen.

“For an American, listening to flamenco like Rosalía’s is much more interesting than listening to conventional rock or pop”

Do you make records to order?

I struggled so much to work in music that I came to an agreement with myself to try to only work on things that I like.

What type of talent attracts you when working with someone?

This is something that I ask myself often. I’m impressed when people have a strong personality. I like to get to know the artist, talk to them, see them play to see if it’s going to work or not.

How would you define your own talent?

I’ve always been motivated to learn new things; this is how I’ve always been. I've been bold, taking risks has never bothered me, and this has helped me to learn even more. So, my talent comes from this boldness, from my motivation to learn and also from an aesthetic that I've had since I was young, a way of understanding things that prevails above everything else.