Javier Perianes

The honest pianist

Javier Perianes, one of the most internationally renowned Spanish pianists, defends honesty when playing an instrument as the key to reaching the audience, over technical skill. A few days after his solo debut at the Palace of Charles V as part of the International Festival of Music and Dance in Granada, a milestone for him, he reminisces about how piano came into his life.

His parents had to sacrifice a lot, “big time”, —Javier Perianes (Nerva, 1978) highlights—, for their son to develop his love for music and, specifically, piano. At Berlin airport —we catch this musician about to hop on a flight—, he remembers the “show” his parents put on to get his first piano into the house and surprise him. So yes, sacrifice, but also plenty of excitement about seeing their son happy. Now, several decades later, Javier has a strong international career which has led him to work with masters such as Barenboim, Dutoit, Dudamel, Mehta or Mäkelä and play with orchestras like the Vienna Philharmonic, the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra or the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Despite his impressive career, Javier assures us he still feels the same excitement and confesses that one of his latest performances, at the Palace of Charles V as part of the International Festival of Music and Dance in Granada —with the collaboration of Iberia—, has been incredibly special to him.

How did your relationship with music start? Did anyone play a special role?

According to my parents, I was quite a mischievous kid. One day, the village band started recruiting people and my mother thought that might help calm me down. I started playing the clarinet, but during some holidays we spent in Islantilla, I discovered the piano thanks to my aunt, who was a piano teacher. My aunt played for me and convinced me that the piano was a unique instrument, I was impressed. I started when I was eight and here I am.

Do you remember the first piano that entered your house?

My first piano was the result of many hours of overtime my father had to do in the mines in Río Tinto. It was an upright piano. When I got home, it was hidden under a blanket and when they pulled it off, there it was. That’s an unforgettable memory. To surprise me, my family put on such a show —they had to block the street and hoist it up with a crane—. My parents did everything possible and more.

“Music isn’t a profession, it’s a way of understanding life. You’re not a musician from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. and then close up shop”

You come from a humble background; did you and your family have to make a lot of sacrifices?

My parents had to sacrifice a lot. And not just for me, also for my brother who studied Medicine. As a joke, we used to call my mother Carlos Solchaga [Minister of Economy between 1985 and 1993]. At the time, a phrase he used to say became famous: “Spaniards, we need to tighten our belts.” Domestically, my mother was a financial engineer. This is how my parents would save for invitations: sheet music, a trip, a course, etc.

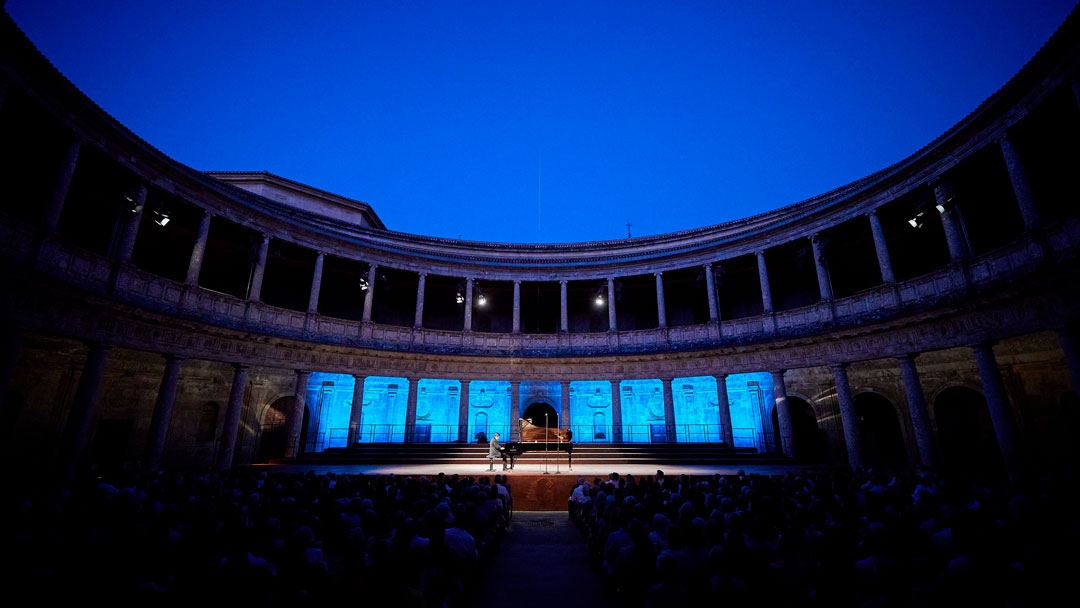

Javier Perianes playing at the Palace of Charles V as part of the International Festival of Music and Dance in Granada. © Courtesy of Ibermúsica

After so many years touching its keys, has the piano become an extension of yourself?

I always say this: music isn’t a profession, it’s a way of understanding life. You’re not a musician from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. and then close up shop. As a great master used to say: “Music attacks you at any time.” It’s a passion that you carry inside, and you can’t disconnect.

Is a pianist’s job as lonely as it seems?

When you do a solo recital, it’s just you and your instrument. But an incredibly special, magical and knowing relationship emerges with the audience. It’s really comforting. Then there’s the loneliness of travelling, where you spend a lot of time alone, but that also gives you the opportunity to nurture your inner world.

You’ve played for great masters, including Daniel Barenboim. How did you feel the first time you played for him?

More than responsibility, I felt grateful to him for making time for me. For someone with his schedule to spend a couple of hours with you is extraordinary motivation, and I treasure his advice.

“Despite getting older, I’m 44, I still have the same curiosity and passion, I’m always eager to learn”

Would you say that the different connections you’ve made throughout your career have helped your talent grow?

I’m sure that all the experiences I’ve had have, above all, helped make me a better person. Obviously, I’ve learnt a lot from great masters in recent years, like Klaus Mäkelä, François-Xavier Roth or Gustavo Dudamel, among others. They are conductors I greatly admire and all the exchanges I’ve had with them have been extremely rewarding. Despite getting older, I’m 44, I still have the same curiosity and passion, I’m always eager to learn.

You’ve travelled across all five continents with your music and have performed at real temples. Do you feel like you receive greater recognition abroad?

No, I’ve never stopped to think about that. I feel fully recognised and appreciated in Spain, where I’ve had the chance to play with practically all orchestras. I also have a close relationship with festivals, like the Granada Festival that granted me their Medal of Honour. I’m extremely grateful to everyone who has allowed me to develop my passion.

In fact, you recently performed at the Granada Festival. What was that night like and what relationship do you have with the event?

My relationship with the festival spans almost 20 years and I’ve attended regularly regardless of the conductor. They have all placed their trust and affection in me. I’ve played there with Tabea Zimmermann, Cuarteto Quiroga, the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra... And we’ve made unique memories. This latest collaboration has been really special because I have made my debut at the Palace of Charles V, an iconic place for me.

“An artist’s talent is a blend of naturalness, flexibility and, above all, honesty. There’s also hard work”

What does talent mean to such a prestigious pianist?

For me, an artist’s talent is a blend of naturalness, flexibility and, above all, honesty. There’s also hard work, but that’s something you can’t capture at first glance. You can be more or less skilled, more or less technically gifted, but talent is also expression. If you leave a recital feeling emotional, if the performance has moved you and you think that’s a special musician, it means they’re talented.

What is the situation of classical music in Spain? Is there talent?

In Spain, there’s plenty of talent. There are many Spanish musicians who are among the first music stands at top international orchestras. There are also pianists, violinists, cellists, flautists (etc.) with international solo careers. Even in terms of orchestra conductors, it’s an amazing time. There’s no lack of talent in Spain, perhaps we have to get better at explaining it, because abroad there are no limits.