Mónica Ojeda

A literary ritual

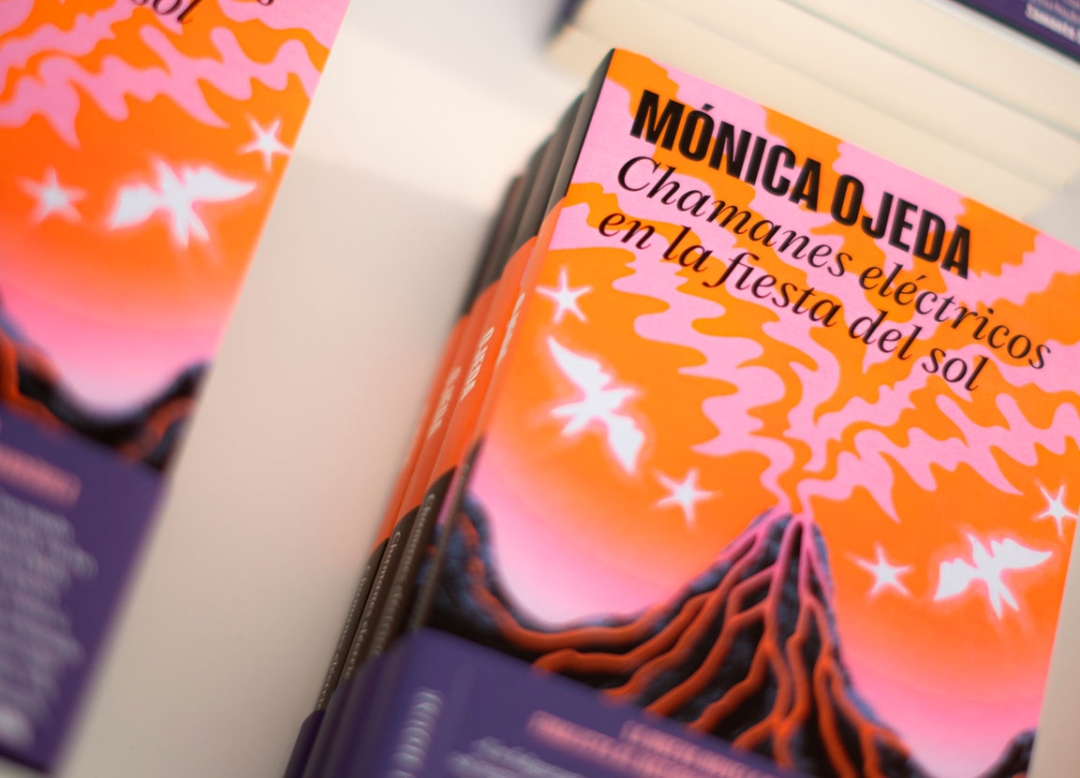

For the characters of ‘Chamanes eléctricos en la fiesta del sol’, the latest novel by Equatorian writer Mónica Ojeda, dancing to the sound of the music at a festival held at the foot of a volcano becomes a liberating ritual, a celebration of life in the context of violence and death. For Madrid Book Fair, another kind of collective experience, we chat to this writer who is managing to steer the focus of literature back towards the Latin-American continent.

Latin-American literature is riding high at the moment, largely thanks to a generation of female writers who have managed to transcend its borders and win over new readers, while receiving plenty of international recognition. These readers curiously flick through novels that, in the words of Mónica Ojeda (Guayaquil, Ecuador, 1988), “bring us together despite the distance.” A place that bridges these gaps is the Madrid Book Fair, an event sponsored by Iberia where this Equatorian writer is chatting to her readers about Chamanes eléctricos en la fiesta del sol, like she did recently at Espacio Iberia. “It’s an exciting time, a friendly gathering that you don’t always have the chance to experience,” she declares. Chosen by Granta in 2021 as one of the top 25 storytellers in Spanish under the age of 35, her latest novel simply reasserts her talent, which, for Mónica herself, “is an inclination of the body that deepens over time and dedication.” She confesses that this dedication has ritualistic elements.

The main characters in Chamanes eléctricos en la fiesta del sol, Noa and Nicole, flee from Guayaquil to attend a music festival. What are they running away from and how can music liberate them?

They are running away from the fear that violence has left in their bodies. They leave a city besieged by drug traffickers. They also come from broken homes. The only thing they have is their friendship and youth, but that is also threatened by violence. That is why they climb the foothills of the volcano, to attend a retro-futuristic festival and remember that they are young girls who have the right to imagine the future. Music, dance, and poetry are movements of the imagination, spaces where the body is capable of being brave and think creatively. The party is always about grief and death: it is the glorification of life despite loss. They go to this party to let go of that fear under the sun.

After the pandemic, people attended concerts in mass and mosh pits are back with a vengeance. Why do you think this is? Do you think we need to feel that closeness, that communion, that community again?

There’s something ritualistic about dancing that I’m fascinated by. Each type of dance has its own possibilities, its own form of storytelling or putting the world into poetry as a space where the body unfolds. Ballet is aerial, classically elongated; flamenco is earthly, using blows that turn the body itself into a musical instrument. Moshing is reminiscent of that universal energy where matter crashes suddenly. The connection between dance and astronomy is ancient: think about the twirling dervish dance, which spins like everything in the universe, for example. Without a doubt, we dance because it is a way to be united with the movement of everything, and because it brings us together and reminds us that imagination is always collective.

“Music, dance and poetry are movements of the imagination, spaces where the body is capable of being brave and think creatively”

At the beginning of the novel, you use this quote by Nietzsche: “The ear is the organ of fear.” How do you inspire emotions like fear in the reader through an art-form that is unable to produce sound?

Written word produces sounds in the imagination. When we read, we hear many things in our head without being fully aware of it. I’m interested in the ear as an organ for the invisible, inner commotion and darkness. It’s a sense that even forces us to close our eyes when we want to listen to a song properly, for example. It connects us to an introspective landscape that we are sometimes scared to approach. We’re never as fragile as when we open our body up to listening: we let everything in, from thunder to voice.

Would you say that conveying the sensations that live music instils to the pages of a book has been the biggest challenge in this novel?

I’m not sure that I aimed to translate the emotion of music to writing in the book. What I did aim to do was to think about what happens when a highly sensitised body due to fear and loss listens to music. Sometimes music makes us cry because we carry the tears inside of us, it terrifies us because we’re already carrying fear inside, it makes us happy because we are already happy, and its rhythm emphasises that. Music, like literature, can open you up and bring out what was buried deep within you. This is why there’s a longstanding tradition that connects music with the hidden, supernatural, shamanic world. Perhaps that was the hardest part to write: for the characters to undergo a nightmarish journey through music.

‘Chamanes eléctricos en la fiesta del sol’ is the latest novel by writer Mónica Ojeda.

For you, is there something shamanic and ritualistic about writing? In a way, you invoke a story and characters.

Yes, I consider writing a ritualistic exercise. Not a sacred ritual, but almost. And for me it’s related to seeking an expression that leads me to a place of change, of transmutation, where some kind of revelation occurs. This is something that always occurs with language. It’s delving into wonder, as Enrique Verástegui says. Slowly. Like a drop of water boring into stone.

“We’re finally reading female authors with the same interest as we read male authors in the past, and that’s wonderful”

There’s talk of a new boom of Latin-American literature and, unlike the previous wave, this one features women. Do you think female voices are listened to more now?

I think we’re finally reading female authors with the same interest as we read male authors in the past, and that’s wonderful. We’re discovering new possibilities in literature. We’re thirsty and, I insist, hungry for delving into wonder.

Do you feel close to other Latin-American female writers in terms of form or background?

I feel close to them in that I believe we have things in common: our political view over our territories, our dark, mythological, symbolic and archetypal collective imagination, our approach to violence and its subtleties, etc. But I think that, formally, our writing is very different. And that’s great. It means that such diverse books continue to be published.

“A reinvented Spanish language broadens the possibilities of language, providing a diverse and wonderful literature that excites us on both sides of the pond”

The Madrid Book Fair connects Ibero-American literary talent. From your perspective, how important are those connecting vessels between Spain and Latin America?

If there is something that connects us intimately, intensely and creatively, it’s literature and art in general. I believe that the Spanish language, for example, is renewed and enriched, even when challenged; because Latin-American writing challenges the impositions on the Spanish language from the most conservative places. It is a Spanish variant that has been influenced by indigenous and African languages. A reinvented Spanish language broadens the possibilities of language, providing a diverse and wonderful literature that excites us on both sides of the pond and brings us together despite the distance. It generates an alternative conversation that is much more horizontal.

Since you started, your talent has received many accolades. Has being labelled a rising star in literature been an added pressure?

No, literature is a game to me. A game of free thinking and imagination. A game that refocuses our view and listening of the world, that is, an important game, but a game, nonetheless. I try to never lose that playful spirit and remember that I never promised anyone anything.