Laura Ferrero

Family of origin

How would you react if, at the age of 35, you saw yourself for the first time alongside your parents in a photo? Writer Laura Ferrero decided to delve into her family history and the result is one of the most acclaimed novels of 2023: ‘The Astronauts’. Tricks of the mind, heavy silences and the lies we tell ourselves were the pieces of the puzzle that had to be put together by the author, a recent nominee of the Goya Awards for the script of ‘A Love’, the new film by Isabel Coixet.

“I had a family, but nobody told me.” This is the first line in The Astronauts (Alfaguara), the latest novel by Laura Ferrero (Barcelona, 1984). At the age of 35, this writer saw a photo of herself alongside her parents, her “family of origin”, for the first time. Why? They divorced not long after she was born, and the traces of that relationship were erased. “It’s not a life-changing discovery, but it does change your views of the past,” she confesses. Laura started delving into that past with the intention of writing a book about that family and she turned to the other characters in the photo, but the answers —or in other words, the versions— shared by his father and her mother weren’t what she expected. “Memory is a trickster. Each person invents a version of the past according to their needs,” she assures us. Her personal journey led to a novel that, since its publication, has brought her endless joy. Recently, she has another reason to smile: being nominated to the Goya Awards for the script of A Love, written alongside Isabel Coixet and based on the book of the same name by Sara Mesa.

The Astronauts sprouts from a family photo. Does inspiration lie in the small details, even if we have to dress it up in grandiosity?

In this case, that photograph wasn’t a small detail for me because I’d never seen a photo of my parents and I together. Imagine. I’m the daughter of one of those couples who got divorced in the 1980s and practically all the photographic evidence of that relationship was destroyed. I realised that I didn’t honestly know where I come from and that was the trigger, what pushed me to write about that family of origin of mine.

You decided to turn to your parents, who offered you contradicting versions. Is our memory unreliable?

No, memory is a trickster. Each person invents a version of the past according to their needs. When remembering a family event, each member remembers it differently and those differences are closely related to what each of them needs to retain. Joan Didion said, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.” When you share part of your past, you often don’t explain how things really happen, but rather how you’d have liked them to happen. And, by telling the same story over and over, we end up believing it; we’re not even aware that we’re tampering with our past.

After the exercise you’ve done with the novel, as children, do we ever truly get to know our parents?

I think it’s hard to really get to know people in general. In the case of our parents, what happens is that we don’t see them beyond that role; we’re unable to transcend that label of mother or father to get to know them better. We rarely consider who our parents were as teenagers, for example. And that’s because the role they play for us is closely related to our needs.

“Memory is a trickster. Each person invents a version of the past according to their needs [...] and we’re not even aware that we’re tampering with it”

Are children the main culprit of this lack of knowledge?

No, both parts are responsible. Parents always try to protect their children and, in doing so, they keep things from them which they could, in all likelihood, totally accept. Sometimes parents treat their children as if they were dumb. In any case, things have changed, in terms of emotional education, for example. Now we’re aware that what’s important is for there to be healthy communication flowing between parents and children.

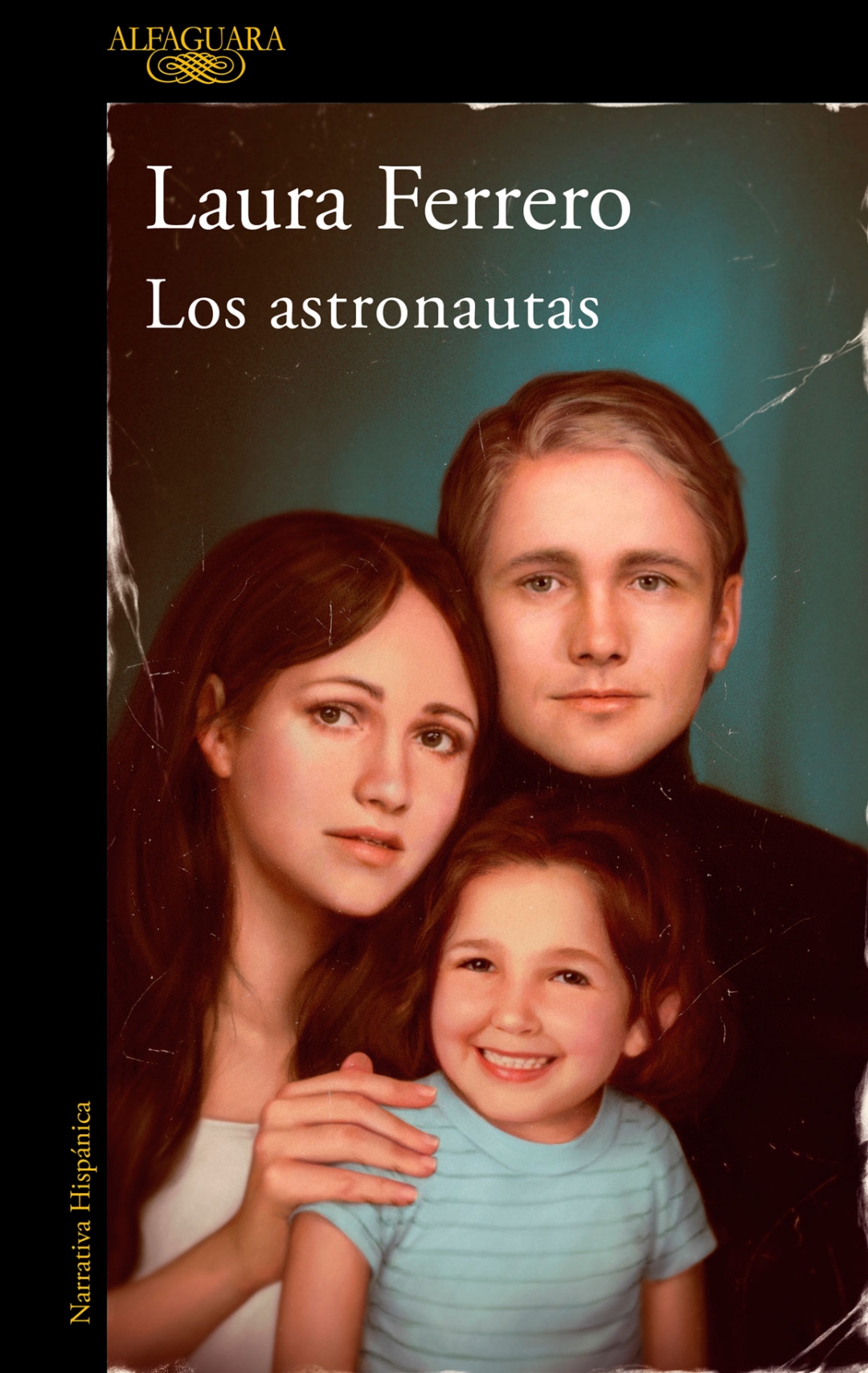

A family photograph, similar to the cover illustration, led Laura Ferrero to delve into her past. © Alfaguara

When she’s a child, the main character in The Astronauts uses imagination to embellish her reality. Something you also end up doing in the novel, which isn’t strictly autobiographical. Should we never give up on fantasy?

Sometimes you have to go really far away to see what’s close to you clearly, and your imagination is a way to go on that journey. The protagonist realises that, if she tells things as they really are, things aren’t going to turn out well for her. Which is why, when they ask her to draw a picture for Father’s Day, she doesn’t draw a father who never comes to pick her up, but rather a father who’s an astronaut. Facts aren’t always useful to tell the story of reality.

Through the novel, you confess that you had hardly any books at home. How does someone who, paradoxically, didn’t grow up surrounded by literature become a writer?

I honestly don’t know... When people say that “children do what they see at home”, I’m not so sure. The only books we had at home were Nobel Prize collections, and I never saw anyone reading them. During my childhood, I used to spend long summers in a village where nothing ever happened and that’s when I started getting into reading; it was a way of travelling without moving and I was extremely happy reading. Boredom played a significant role. Now we’re overstimulated to avoid feeling bored, but boredom promotes creativity because it allows you to think, which is difficult at our current pace of life.

You had to self-publish your first book (Piscinas vacías). Is it that hard for people to give you a chance in the world of publishing?

Many factors play a role. It’s tough if it’s a short story collection instead of a novel, as was my case at the time. I worked at a publishing house, and I knew the process I had to follow to get published, so, when I was told that my short stories were really good, but to try writing a novel, I thought about self-publishing. It’s also hard if you don’t know anyone who can get your novel to the right person. Editors are always overwhelmed with manuscripts.

“We often say someone is talented, but what do we really mean? It’s a word with many meanings and applications”

You’ve written the script for A Love alongside Isabel Coixet. What is it like to adapt a writer with such a personal universe as Sara Mesa?

I love Sara Mesa, so it’s been wonderful to adapt her novel. Her universe and mine aren’t so dissimilar, so it’s been easier. Her novels make me uncomfortable, they lead me to feelings I don’t go through when I write, so as a writer I haven’t felt the urge to change anything. In the end, it’s Sara voice that prevails —her voice and intention are there— and I like that.

You’re also a literary critic. Are you your biggest critic or when it comes to yourself do you refrain from doing so?

I think I’m quite critical in general, also with myself. But there’s no distance when judging your own work, that is, you never know if what you’ve written is a masterpiece or a mess. So, when I really want someone’s opinion, I ask my editor. She’s someone who assesses the material that you’ve been working on for a long time with fresh eyes and from the outside.

Finally, what is talent to you?

I’d never given it any thought, so I’d have to think about it... But I will say one thing: even if I’m not sure how to define it, I can tell when someone is talented. We often say someone is talented, but what do we really mean? It’s a word with many meanings and applications. Talent is an innate ability, something like a gift, and being talented is a challenge but, above all, a responsibility: to develop it.