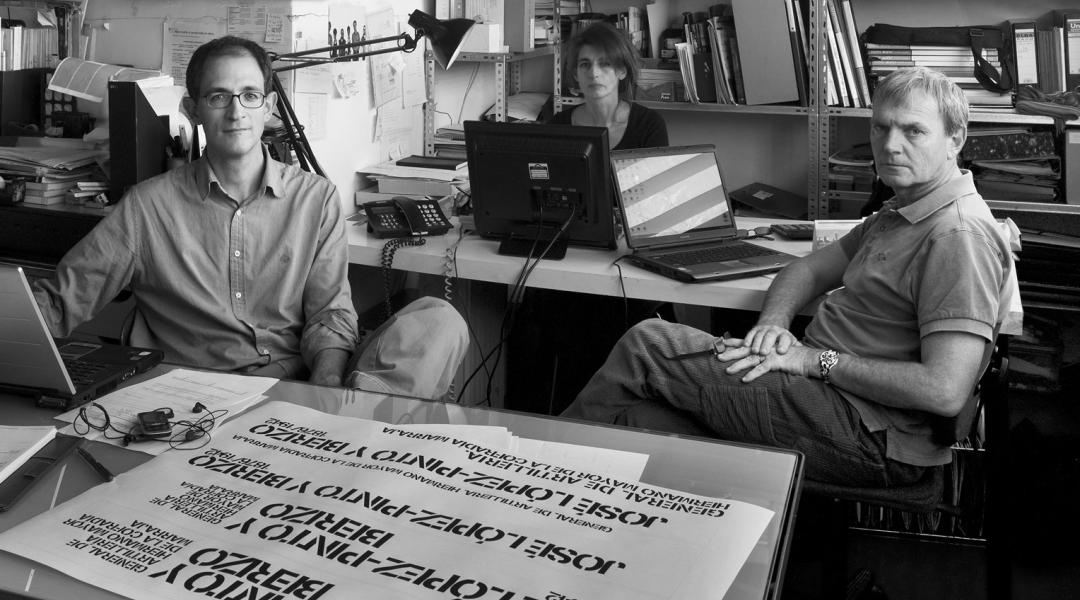

Andrés Cánovas

Principled architecture

The design of the Spain Pavilion at the Dubai World Expo is founded on the idea of people and places. Designed as a space for tranquillity and reflection, this work by Amann Cánovas Maruri seeks to promote sociability and calls on sustainability, built on commitment, beyond the climate. Led by Andrés Cánovas, one of its founders, we enter a studio, recognised with more than 70 national and international awards, which offers ways of moving through the present day through new architectural realities.

Where the shadow begins. These are the instructions to find the Spain Pavilion at the Dubai World Expo. A string of squares, where time seems to stand still, designed for rest and reflection. “The difficulty in this kind of project lies in not losing sight of the fact that, in the face of pure performance and given the unavoidable staging conditions, it’s possible to offer visitors a smart and friendly place to take shelter in with dignity,” they share.

Andrés Cánovas (Cartagena, 1958), one of the office’s founders, tells us about a sustainable project in the broadest sense of the word. “Given the breakneck speed that contemporary society lives at, a set of spaces that make room for slowing down is nothing to be scoffed at, and given the rush to absorb everything we find, the fact that the Spain Pavilion offers some calm is no bad thing. This was one of our challenges.” But was it the only one?

Beyond the Spain Pavilion’s functionality within the Dubai Expo, does this project offer a critical or reflective view of contemporaneity?

We wanted to move away from the architectural concept that abounds in Dubai and the amazing technology these countries work with. It seems odd to talk about sustainability while at the same time dealing with buildings that need to be cooled and heated mechanically using expensive polluting systems. Thought went into studying the architecture that has been carried out historically in other places and designing a pavilion with certain passive conditions. It’ll work with very little mechanical ventilation: the shape of the building and the way it is structured will be an advantage in that climate and region, and its carbon footprint will be as small as possible. If current architecture doesn’t support the great climate revolution, we’ll be looking the wrong way.

“If current architecture doesn’t support the great climate revolution, we’ll be looking the wrong way”

The terms for sustainability are expanding; in which direction should architecture evolve?

The word “sustainability” is very worn out, but that doesn’t mean that we should stop paying attention to this issue. I prefer to use “caring architecture”, which works for the territory and the climate, but also for people. But there’s another kind of social sustainability. The pavilion, for example, has no doors —only for the exhibits— and works like a public square. This is a kind of architecture that talks about society and about preserving conditions that have granted our countries with a certain degree of sociability. The square is one of those social spaces, where we sit, gather, have coffee, or read the newspaper. We should get used to contemplating other definitions of sustainability, beyond the climate.

You mention the square, a key space for the civilisations of Antiquity; are these cultures a source of inspiration?

Of course, we are an evolving species. Our own biology examines the past, our genetic code, and outlines an evolution. Culture can’t be understood without looking back either, but it can’t stay there. It involves creating a new present inspired by the past.

This contemporaneity can also be found in many of your buildings, which have been chosen as the backdrops for videos by artists such as Love Yi, Ayax, or Hinds. Where does this phenomenon come from?

When we realised it was something that kept repeating itself, we became interested in studying how certain works connected with a certain part of the population, especially incredibly young people focused on musical genres, like trap or rap, that weren’t closely related to us. This led us to believe that there was a connection with architecture not just as an object, but as part of a relatively contemporary urban landscape. And we were attracted to this idea, knowing that what they were essentially choosing was a residential style.

The pandemic has revealed the radical change that current housing styles need to undergo; how do you envisage this change? Which actions are you carrying out in this sense?

Society is far ahead of architecture. There are social changes that architecture, a discipline that is deeply reticent to change, hasn’t been able to take on. What we do know is that the housing models that we’ve been working on aren’t extremely contemporary. Management models have appeared that make collective housing start to look different: our relationship with the climate and the planet, women’s empowerment. A home designed for a family is remarkably different to a home designed for people, regardless of how they gather as a family. These won’t be strictly family homes, rather spaces that can be adapted to different living conditions.

“Society is far ahead of architecture. There are social changes that architecture hasn’t been able to take on”

How do you identify talent within your profession?

There’s an important word that, sometimes, isn’t taught at architectural school, and that is “commitment”. An architect must be committed to their profession, just like doctors or lawyers, when it comes to their service to society. This work is linked to other disciplines, such as sociology, philosophy, or the visual arts, and education shouldn’t be strictly technical, rather both technical and humanistic. In this sense, our schools do a decent job and are different to those in other European countries. Good architects graduate from them and, after training, will choose their level of commitment: if it’s low, their education will be of little use; if it’s high, it’ll be a tool to practice with.

Competitions are part of your everyday life, are they the key to building change?

90% of our work has been through public tender, which is something that allows us to outline conditions over projects that aren’t subject to the inertia of the present. They push us out of our comfort zone. I believe that repetitiveness, falling into routines, is the worst thing that can happen to us. So, escaping the daily grind and thinking creatively is essential, and tenders favour this because there is competition. The intellectual and material efforts that they entail are staggering, but they’re also a tool for transformation.

What challenges will your office face in the coming years?

That is, not taking too much notice of our career; the only thing that matters is our next job and our commitment to it, no matter how small the project. Our focus is based on believing that a dog kennel requires the same effort as the Spain Pavilion at the Dubai Expo. There are no first or second-class jobs, rather commitments with society.