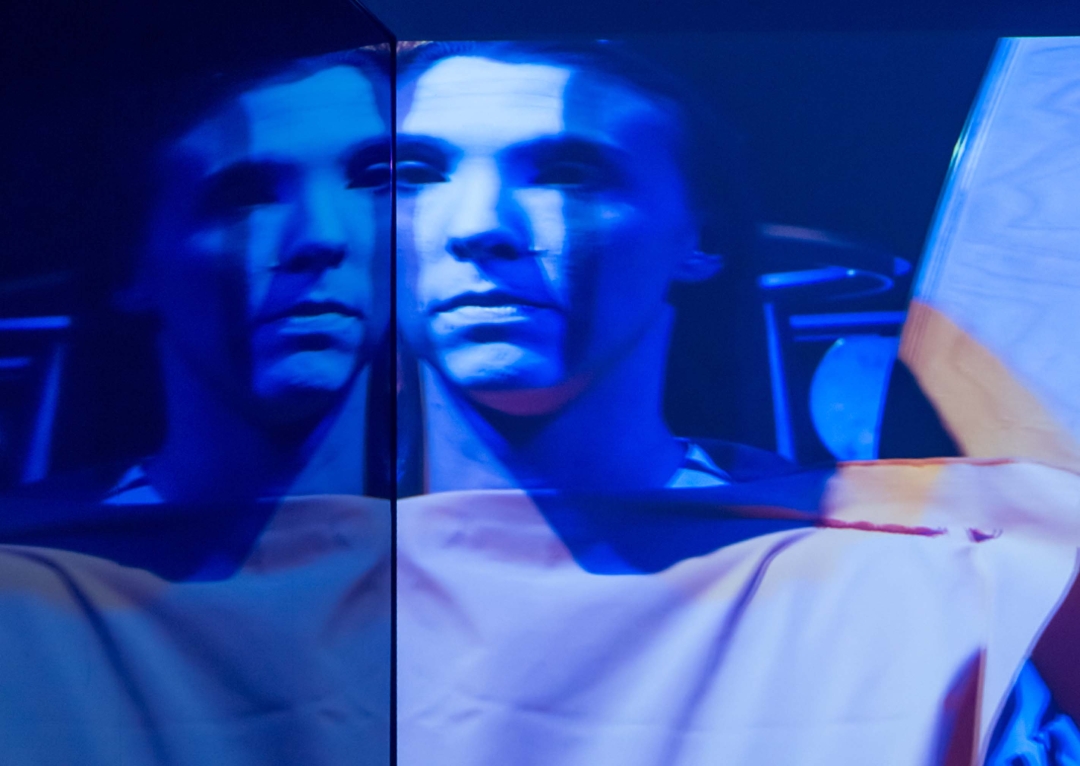

Leonor Serrano Rivas

A magical gaze

The relationship between magic, science, and philosophy has driven artist Leonor Serrano Rivas to rebuild contraptions —such as the music box, camera obscura, or magic lantern— that inspired a renewed vision of the world in the 16th century for her new installation. The ‘Natural magic’ exhibition, belonging to the ‘Fissures’ programme at the Museo Reina Sofía, can be visited until the 27th of February.

Thirst for knowledge has been a constant in human life. In the 16th century, science, magic, and philosophy came together when several artists started to work on designing devices that opened up paths that had never been explored until then. Their goal was to suggest new ways of generating knowledge and finding answers to big transcendental questions. Leonor Serrano Rivas (Málaga, 1986) pays homage to those artists and updates her discourse at a time when returning to our origins seems extremely timely. Natural magic is an exhibition that ensures a bright aesthetic experience and that relates to the visitor in a very special way.

Where does the journey into the past that you set out in the exhibition begin?

I’ve always been interested in structures that include theatrics, and these come from the Renaissance era. The artists of the 16th century, whose devices make up Natural magic, play a significant role in creating the scientific knowledge that has reached us. I had been researching this for some time, so the invitation from the Museo Reina Sofía to take part in the ‘Fissures’ programme came at the perfect time.

What talent did these artists have? How did they inspire you?

When creating their contraptions, the intention of those artisans was to provide an alternative view of the world. I love that, and I understood that looking at the origins through them was like retelling the story of all that knowledge. The power of art lies in bringing things closer to you from a different angle, creating another perspective.

“The power of art lies in bringing things closer to you from a different angle, creating another perspective”

More than visitors to the exhibition, you talk about spectators. What role must they play in it?

Gonçalo Tavares, an author I follow closely, says in his book Voyage to India that people have three ways of approaching objects —he calls it the line of the gaze’s level— and I’ve tried to articulate this idea throughout three rooms. In Space 1, the spectator doesn’t need to change their point of view to contemplate the objects and, they even become part of the film we project. In the Vaults Room it is suspended from the ceiling, so you have to look up. And in the Protocol Room, the floor tapestries force you to look down. This subtle and unconscious performative movement changes the way you face the piece and the representation of the world.

Which criteria have you followed when occupying the rooms and placing the objects?

The idea is that each piece connects with the next, for there to be a narrative. Each object represents a specific moment, but there’s a running thread. Even though there’s no itinerary, I designed it as a storyline with three chapters where the audience moves from darkness towards the light. There’s an object presiding each room. Space 1 contains the camera obscura, the Vaults, the magic lantern, and the Protocol Room, the music box.

You studied and lived in London, but you also spent time in Tokyo and Tangier. What did travelling to those places and discovering different cultures bring to you?

My English period was really important because I spent eight years in London and Oxford. It was a huge change in comparison to Spain, because the education in English-speaking academia is completely different, and they have other role models. I was also in Tokyo for a few months, and I’ve done residencies in Tangier. It’s hard because you’re outside of your comfort zone, but they’re productive experiences at a professional level, because they bring you closer to forms of production where the rules of the game are different. You’re like a child approaching the world for the first time, and you try to understand how to move within it.

“There’s something beautiful about artistic practice: you can be all the people you want. You have to let yourself play”

What motivates you about your work?

We’re artists out of spiritual and emotional need. It’s odd, but you feel like you can’t do anything else. You work with conviction. You’re interested in getting closer to things you don’t know about and there’s something beautiful about artistic practice: you can be all the people you want. You have to let yourself play. It’s a mixture of spiritual impulse and technical curiosity.

Apart from the installation, what other artistic techniques do you usually work with?

The installation is a way to show my interest in architecture [Leonor also studied this degree] and spaces, but I try to not have a preference. In my case, the idea leads me to the medium and not the other way around. I feel fascinated about new techniques. For example, I’ve done glass blowing and glazing. I also really enjoy the film shooting process because it’s completely different to my day-to-day life; it contrasts with a much more reflective and solitary life in the studio.

“Talent is being able to provide a vision that creates a new space for imagination in others”

Finally, how would you define talent?

In my case, talent is being able to provide an alternative image of the world, a vision that creates a new space for imagination in others. I think this is really relevant right now.