Juan Carlos Bracho

Space, Relativity, and Plenty of Good Ideas

Artist and draughtsman Juan Carlos Bracho explores the relationship between space, time, and perception in the exhibitions Architecture and the Self, on show at Sala Alcalá 31, and Tutti Frutti, at the Alcobendas Art Center. Two interdisciplinary exhibitions showcasing drawings, installations, videos, and photographs in which the Cadiz-born artist again places viewers at the center of the artistic experience.

Far from many of his contemporaries, the work of Juan Carlos Bracho (La Linea de la Concepción, 1970) doesn’t seek complacency in the eyes of others. Nor the effectism that, in an era in which images reign supreme, emerges in galleries and contemporary art fairs every year. His creations speak of an art whose starting point is the germ of ideas, an art that develops slowly in a time and a space that are subject to endless constrains, in other worlds, life itself.

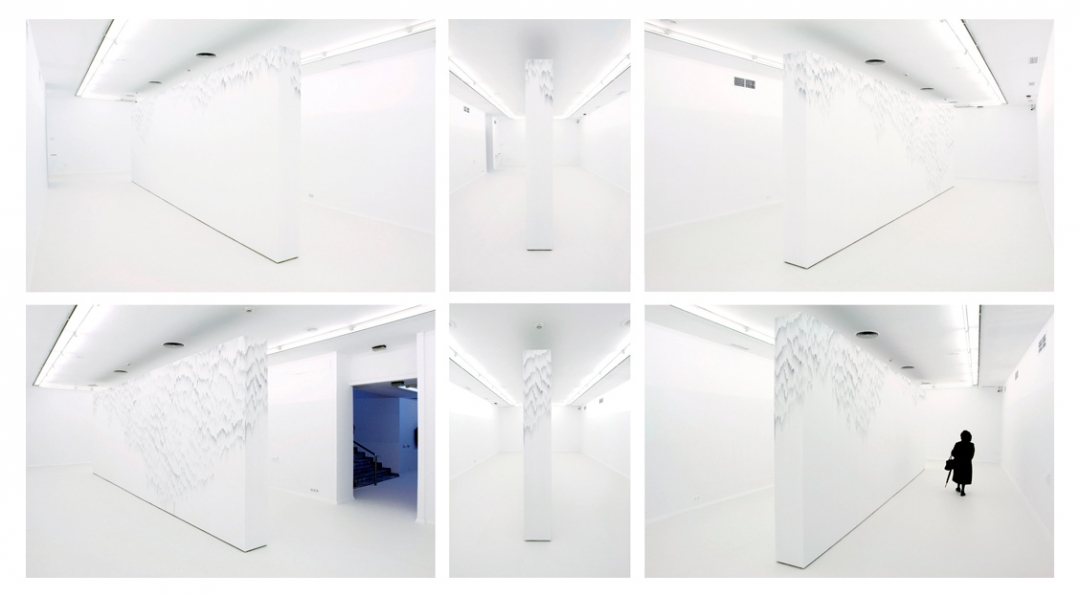

Bracho's work moves on intangible and subjective territory, between minimalism and conceptual art. His pieces take on a new meaning depending on who is looking. He calls it “experience through experience.” His drawings, mechanical and sometimes hypnotic, invade spaces in which error and chance are understood as part of the artistic process. This is reflected in his recently inaugurated exhibition Architecture and the Self, running until February 2 at Sala Alcalá 31, a show that invites visitors to inquire into their own perception of space and beauty.

Your exhibition at Alcalá 31 showcases a set of pieces revolving around your personal (and spatial) relationship with architecture, a theme that is present throughout your career. What has been your greatest discovery in this direction so far?

Above all, I’ve come to understand space and time, two closely related coordinates, as a mental process. Everything is relative, and it only depends on where you are, on the coordinates you choose in relation to the time and the space that surround you. For example, on an airplane time goes forward or backward; you can be either inside or outside, up or down. It all depends on your perspective.

Like the setup of the exhibition, projected as a huge installation, artworks like the sculpture Now and Forever seem to be aimed at engaging viewers in a dialogue, forced somehow to fit the pieces together to reach a conclusion. What role do viewers play in your work?

The viewer's gaze is what gives meaning to my actions. I’m just a mere executor. The result of my work, which belongs to the process itself, is the repetition of minimal graphic elements such as lines, dots, strokes, and frottages [graphite’s own dust] which are gestures in their expression. The resulting image and its meaning belong to the viewer. It all depends on what the individual viewer is willing to give.

'M sobre M' (Sketch for an Intervention), by Juan Carlos Bracho. © Courtesy of Sala Alcalá 31

Some of the pieces are made with people from your inner circle. For example, Hole For is made by the person to whom For Adam is dedicated; and M over M was done together with your partner. What is the idea behind this creative symbiosis?

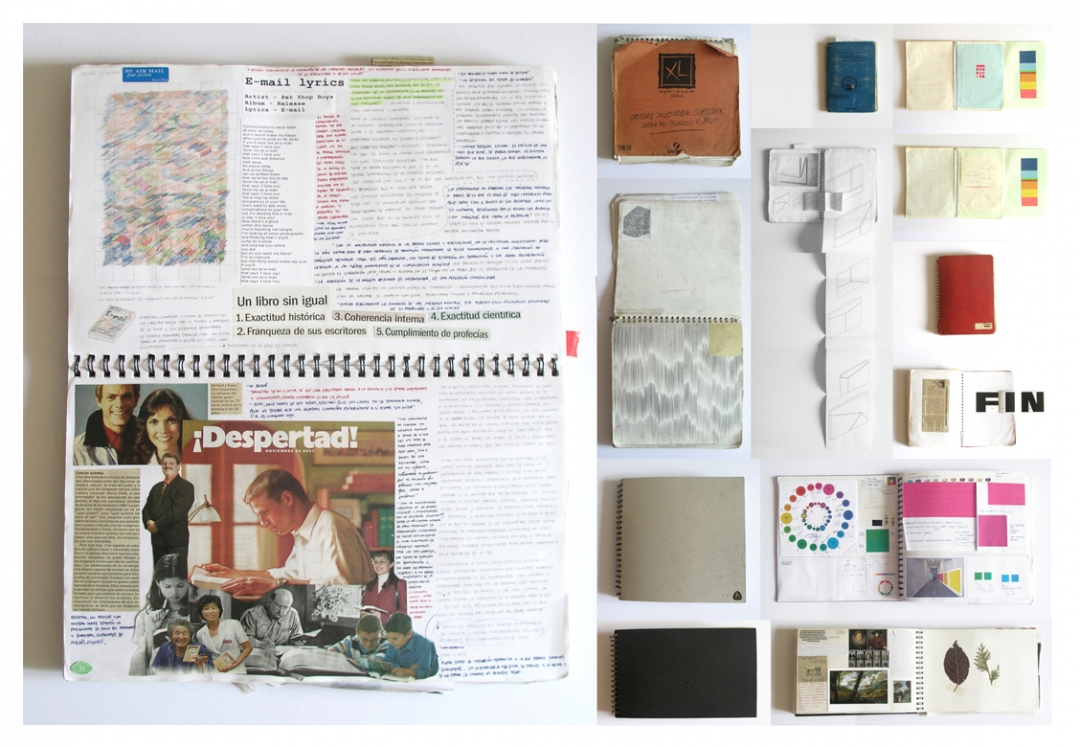

Before this exhibition, I had made all my drawings myself for practical reasons, since they lack the auratic charge that is traditionally attributed to the figure of the artist. It's me, but it could be any of us. In the cases you’re referring to, the idea was to add layers of action and emotion. It’s about highlighting the technique itself, drawing as appropriation, copying myself or through the eyes and the hands of others. Moreover, working in a team is always very rewarding and enriching.

The process or the creative journey is crucial in works such as Golden Geometry for EC and Films About Myself, in which the passage of time, chance and the participation of external agents (objects, people) have been and remain being part of their creation. Do tell us about it.

My works usually go a long way before they’re finished. They are simple to make but require great concentration and discipline. I like to document these actions because, being so immersed in them, sometimes I’m not aware of the parallel narratives that occur around me or in my absence. In the specific case of Geometry, my intention was to reveal the network of common interests, the shared space, the layers - often invisible - that shape the meaning of every work of art.

Sol Lewitt said that “The idea itself, even if not made visual is as much a work of art as any finished product.” I feel this has a lot to do with your work. Do you agree?

Absolutely. A work of art is what you want it to be: the work of the artist, an aesthetic reflection on the world of ideas, the ideas themselves... The work of art exists from the moment you think it, share it, or simply draw it in your mind or on apiece of paper. Then it takes shape, or not. In this exhibition and throughout my career there’re projects that have taken years to complete or formalize, that have mutated, branched out and materialized, or maybe not, but they exist.

Sculptural set 'Now and Forever’, by Juan Carlos Bracho. © Courtesy of Sala Alcalá 31

You use other techniques such as photography, video, and muralism, but you’re known specially for your major use of drawing. Do you feel comfortable with being tagged as a draughtsman?

Yes, of course, but what is drawing? To draw a line on paper, to reproduce an object, an idea, to move, to dance... It can be something physical, tangible or mental. Drawing is the simplest tool, yet it’s complex. Drawing well, drawing badly. I don't know if I will be a good draughtsman from an academic viewpoint. I think drawing and art in general entail attitude, and my drawing style has plenty of that - of action, appropriation, constancy, discipline ...

At Alcalá 31 there’re many works done ex profeso and in situ. Could it be said that’s ephemeral art?

That’s what I thought until the completion of my project Memories of Love, on show in this exhition. It’s a kind of archeology of my own work, but now I know that my drawings aren’t ephemeral, they just stop being seen, but they exist. Is only what we see real? I don’t think so. All the works made directly on the room’s walls will remain there forever, whether we see them or not, in a latent state. These in particular will also exist physically, since the graphito’s dust, the pencil’s chips, the masking tape used to delimit the drawings, along with other remnants — "the drawing’s negative” as Armando Montesinos, the show’s curator, calls them — will be donated to the Community of Madrid.

The author's work diaries. © Courtesy of Sala Alcalá 31

Además de la exposición en Alcalá 21 expones estos días Tutti Frutti en el Centro de Arte de Alcobendas, donde estudios de color ocupan la mayor parte del proyecto en una amplia reflexión sobre el error. ¿Qué significado tiene para ti el acto de errar en el arte o en la vida?

El error y el fracaso forman parte de todo proceso vital y creativo. Pero en una sociedad, la nuestra, dominada por el capital y el producto, se elimina y se discrimina, no interesa. Pero cuando te equivocas, cuando fracasas, ¿qué queda de toda esa experiencia? En esta dirección invito a los lectores a ver una de mis piezas videográficas como reflexión. Se trata de La boule de beige. Historia de un fracaso. Está en internet. ¡No digo más! (ríe).

¿Cómo afrontas esta temporada entre tanto proyecto?

Con mucha energía e ilusión. Me siento un afortunado.