Chillida Leku

Second Parts that are Actually Good

After being closed for eight years, the Chillida Leku museum has reopened its doors. The spectacular home where most of Eduardo Chillida’s work is showcased was selected by ‘Time’ magazine as one of the greatest places in the world to visit.

Eduardo Chillida was looking for a home for his works where future generations could meet and experience his art in a unique location. And that place, leku in Basque, which he established himself in Hernani, San Sebastian, where he spent a large part of his life, has recently been included in Time Magazine’s World’s Greatest Places 2019 list, Chillida Leku being the only Spanish representation on it.

The magazine is not the only one to attest that it is a unique and essential place—so are the over 45,000 people from across the globe who have visited the museum since its reopening last April, after being closed for eight years, thanks to the agreement reached between the sculptor’s heirs and the Hauser & Wirth art gallery. Chillida Leku is home to the largest and most representative collection of the artist’s work—an outdoor sculpture site and exhibition space inside the Zabalaga country house—a traditional, 16th century Basque construction. “This distinction by Time magazine has a double meaning. It is the recognition, on the one hand, of the work and the enthusiasm the team has put in the opening, something we have done with all our hearts, and, on the other, of the work and vision of Chillida placing the museum in the area where he came from, but with an international character,” says Mireia Massagué, director of Chillida Leku.

The new Chillida Leku is very faithful to the previous one. Thanks to the good general condition the facilities were in, there has been no need for a total renovation, but rather a careful update, directed by Argentinian architect Luis Laplace in close collaboration with architect Jon Essery Chillida, the sculptor’s grandson. The country house—the museum’s central building—retains exactly the same appearance and structure Chillida conceived, but has been equipped with improved lighting and better insulated floors and ceilings, as well as adequate accessibility for people with reduced mobility.

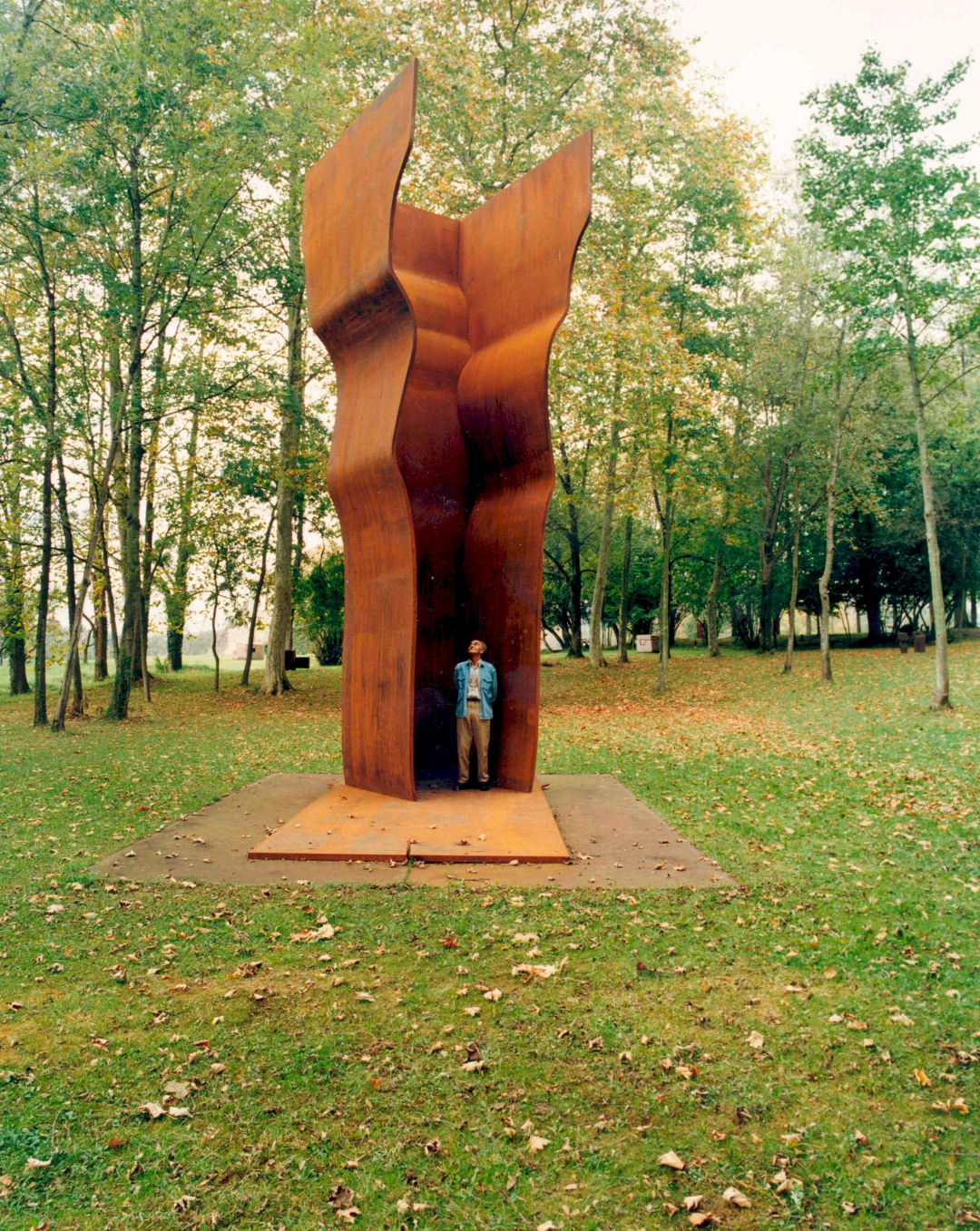

Eduardo Chillida inside his 'Searching for Light I' (Corten steel, 1997) in the early stages of the work’s oxidation. © Zabalaga Leku. San Sebastián, VEGAP, 2019. Succession of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stephan Erfurt

In addition to these improvements there are several new facilities, such as a visitor welcome centre, the Lurra cafeteria, and a shop, while the parking lot has been renovated as well. The project also features the contribution of Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf, pioneer of the New Perennial movement, who has introduced subtle landscape elements.

Furthermore, so as to leave the museum’s unique nature virtually undisturbed, there are hardly any signs or explanatory panels in Chillida Leku. Instead, twenty of the sculptures located in the gardens, as well as ten works exhibited inside the country house, are accompanied by a QR code that, when scanned, allows visitors to access information regarding the pieces. As Mireia Massagué points out, “we have carried out a renovation that is not noticeable. What we have done is improve the visitor experience, making it more special. And, without a doubt, one of our big commitments is to devise a very powerful program with which we can set ourselves apart from the previous era, and go for the local public. We want the local visitor to be our friend.”

"One of our big commitments is to devise a very powerful program with which we can set ourselves apart from the previous era, and go for the local public"

The first exhibition of this new chapter could not be other than a retrospective of the artist. Titled Eduardo Chillida. Echoes, the inaugural exhibition is curated by Ignacio Chillida and the museum’s research team, and brings together more than ninety pieces, tracing a complete path that goes from the late 1940s—when he started drawing—to the year 2000, including the discovery of iron as raw material for his work and the development of his very personal language. The exhibition features pieces in iron, granite, alabaster, plaster and paper, without leaving out significant works such as the Gravitation series (paper sculptures where relief and emptiness take on special importance) and the Lurras and Oxidos (pieces made with chamotte clay).

The title of the exhibition refers to the sculpture Oyarak (Echoes, 1954), a piece that is exhibited on the country house’s ground floor. The word echo refers to the idea of repetition, something closely related to Eduardo Chillida’s working method, focused on creating series of works that started from the same concept. The name Echoes also alludes to the very sonority of the sculptor’s sculptures, which emit sounds that move through space.

Echo is also what the museum is looking for, since, as Mireia Massagué points out, “the meaning of Chillida Leku is to connect with the territory and the local artistic fabric. In fact, this summer we have already collaborated with the Botín Centre, in Santander. We want this, the Cantabrian area, to be linked not only to gastronomy, but also to culture, since we have the means to make that happen, such as the aforementioned Botín Centre, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, the Balenciaga Museum, and the Guggenheim.” The echoes of Eduardo Chillida can be heard today better than ever.