Virginia Feito

The weird charm of darkness

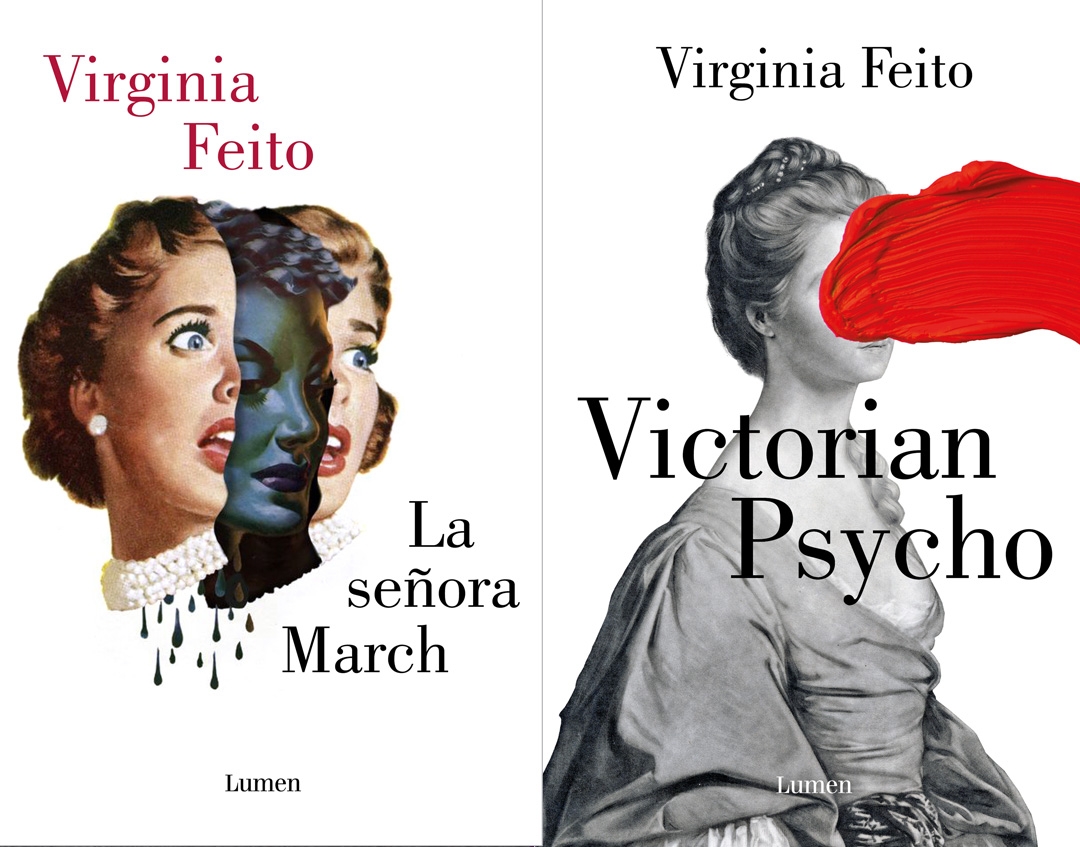

Writer Virginia Feito has made one of her literary dreams come true: to bring a psychopath to life. This is the case of Winifred Notty, the disturbing protagonist of her second novel: ‘Victorian Psycho.’ A fearless governess who strips the miseries of Victorian society in a dark, witty, and bloodthirsty thriller. Proud of her creation, she enjoyed meeting her readers at the Madrid Book Fair.

When she was little, Virginia Feito (Madrid, 1988) was already writing stories on her mother’s typewriter. Her calling was clear and, despite a slight detour into the world of advertising, that itch was always there. Her first novel, Mrs. March, turned into a publishing phenomenon… In the US! “People are surprised that I write in English, and that’s normal,” she confesses, but there’s a reason for that: Virginia was educated in English, she started reading in English and, therefore, feels more confident writing in English. People say that your second novel is the hardest to write, and Virginia confirms this with her characteristic dark humour: “I had a spot of trouble and almost got in the sea and carried on walking.” Fortunately, she decided to turn around and finish Victorian Psycho. With Winifred Notty, a governess capable of making you laugh in one paragraph and your blood run cold in the next, Virginia has made one of her dreams come true: providing literature with her own psychopath. The peculiar psyche of her protagonist is one of the topics of conversation during her signings at the Madrid Book Fair, an event sponsored by Iberia. Readers long to see the adaptation of her two novels on the big screen—Hollywood bought the rights to both of them—, a yearning shared by the writer herself: “I hope it comes out soon because it seems harder to make a film than to publish a book!”

You had a promising career in the world of advertising and decided to leave it all behind to work on your writing. Was this your true calling?

Undoubtedly, writing was my calling. I started writing stories on my mother’s typewriter when I was little. When I graduated from university, I thought: “What now? Do I go home to my parents to write a book?” It didn’t seem realistic to me, in fact, it seemed irresponsible, so I tried to find something that involved writing and creativity, but in an office with a salary. Advertising was fun and motivated me, I didn’t hate it by a long shot, but over the years my true calling knocked on my door again.

What pushed you to start your literary career with a “Once upon a time” instead of the Spanish equivalent, “Érase una vez”? Was it a conscious or unconscious decision?

It’s weird because it’s not my mother tongue—neither I nor my parents are native speakers—, but I’ve always had a relationship with the English language. I lived abroad when I was young, and since then, I read almost exclusively in English. When I started writing, I tried to imitate my favourite authors, and they were all English-speaking. Even today, I find Spanish imposing because I don’t feel confident, and to write a novel I need to feel comfortable.

“Even today, I find Spanish imposing because I don’t feel confident, and to write a novel I need to feel comfortable”

You’re a Spaniard who writes in English and got published in the United States first. Which talent do you think they detected in that first draft of Mrs. March?

The truth is that I don’t know, I’d like to ask them one day (laughs). It was a struggle because in Spain, authors tend to deal with publishers directly, but in the United States and the UK, you cannot reach them without an agent. I had a list of agents and sent my manuscript to a few of them. I can’t remember the exact number, but I was rejected several times before someone saw something in it. What did they see? The novel included ingredients that were trendy at the time, like a thriller with a female main character, but it also had a distinctive style that intrigued them. They probably also thought: “I can sell this” (laughs).

They say a prophet is honoured everywhere except in their own hometown, but you’ve also managed to succeed in Spain. Do you enjoy visiting the Madrid Book Fair and spending time with your readers?

Yes, I love it. I enjoy it more every year. We writers aren’t very adventurous, and the fair is our time to shine. We face high temperatures and gale-force winds to be with our readers. I’m being a bit extravagant with this metaphor (laughs), but it’s really exciting, and I always receive a lot of love. The fair raises my spirits because it boosts my ego.

‘Mrs. March’ and ‘Victorian Psycho’ are the two novels published by Virginia Feito. © Lumen

After the success of Mrs. March, did you feel pressure about your second novel?

So much. I wrote the first draft after the success of Mrs. March, and it felt like I was flying. I thought, “I’m brilliant and can do anything.” I was overconfident, but my agent, my mother, and people around me read it and told me that it wasn’t as good as I thought. They told me that it had great ingredients, but that it needed more work. It was a major blow. I don’t like criticism, call me crazy (laughs), and I suffered a crisis. I edited it a lot: in third person, first, in past tense, in the present, I removed things, put them back in… I didn’t really know what to do, and I panicked.

Speaking of Victorian Psycho now; why has the figure of the governess been featured in so many great works of fiction? What caught your attention?

I liked the fact that, in those times, they sort of lived in limbo. They didn’t belong to the upper class, but they weren’t servants either. They tended to be women who, for various reasons, had to start working. They had to adapt to a family, educate their children, repress any thoughts or behaviours that were frowned upon, and keep quiet about all the disgraces and injustices they saw. I think she’s an intriguing figure who adapts well to drama and has a lot to give to a story.

You’ve confessed a certain fascination for psychopaths. What pushed you into the mind of one?

The psychopath is a literary figure that I love, and I always knew that I wanted to create one. How the mind of a psychopath works is fascinating. For a human being to not feel fear or blame must be liberating, even attractive, but on the other hand it’s terrifying for life in society. Each psychopath I discover in novels catches my attention, and I was thrilled to create my own, to make my small contribution to this type of character, and for her to become part of literary history.

“Each psychopath I discover in novels catches my attention, and I was thrilled to create my own, to make my small contribution to this type of character”

Your novels seem like they are made to jump onto the big screen. In fact, Hollywood knocked on your door, and you’re working on scripts for both adaptations. Why do you think this is?

I think I have a very visual style, and I can’t help it. I can’t imagine an action in a non-visual way; I see it as a film in my head so that I can describe it. Obviously, literature allows you to describe things that film cannot, but from what I’m told, my stories are easily adaptable and can work onscreen. There are wonderful and incredible novels that are very hard to adapt because you don’t know how to even start to translate them into a purely visual language.

You’ve been compared to masters of suspense like Patricia Highsmith or Shirley Jackson. How do you feel about these comparisons? Are they your role models, or do you have others?

I don’t take them very seriously because, obviously, the talent isn’t comparable, but on the other hand, it gives me a thrill. Shirley Jackson had a significant impact on me when I read her and indeed, she’s a role model. I’ve always loved Patricia Highsmith, and she wrote one of the most famous psychopaths in the history of literature, Ripley. But I feel more inspired by the darker humour of some of her other works, like Little Tales of Misogyny. I’d also quote Bret Easton Ellis, author of American Psycho. And I cannot forget about Charles Dickens because he was the first author that I tried to imitate when I was little… I was obviously a very pedantic child (laughs).

For your third novel, would you like to explore other genres, or do you feel comfortable with suspense?

I don’t know if I’d qualify my novels as strictly suspense. Both Mrs. March and Victorian Psycho blend different genres, and I like that they are hard to classify. I don’t think I’ll be able to avoid writing about something dark… It livens things up (laughs). I’m not sure if I’d know how to create conflict without something disturbing at its core. In terms of exploring other genres, that doesn’t scare me, in fact, I’d love to change and feel like I’m doing something different.