Pol Guasch

The kaleidoscopic writing

The Festival Eñe Talento a bordo Award, created in collaboration with Iberia, has been granted to Catalan writer Pol Guasch. With two poetry collections and one novel under his belt, the jury has highlighted the maturity of his gaze and his experimental audacity. His writing, which he himself defines as “deliberately complex and kaleidoscopic”, makes him one of the most promising literary authors of his generation.

Pol Guasch (Tarragona, 1997) is the first winner of the Festival Eñe Talento a bordo Award, which seeks to recognise new literary voices in Spain. This young 25-year-old, who published his first novel in 2021, titled Napalm en el corazón (which joins two poetry collections: Tanta gana and La parte del fuego), prefers to talk about work, which leads him to persevere, despair, and enjoy himself every time he sits down to write, than about talent, which he sharply describes as “a lie”. But his talent is undeniable, as the members of the jury noted: “Guasch’s writing combines a mature gaze with experimental audacity without losing sight of the generational conflicts and anxiety of an unstable and everchanging world, something that singles out his work and makes him one of the most intriguing literary voices on the current scene.” He talks to us just a few days before receiving the award on the 19th of November at the Círculo de Bellas Artes.

Do you remember the first time you felt the urge to write?

I always say that I came to writing by accident. What I mean is that I don’t feel like I chose writing. I think I came to writing as someone who reaches an unknown place knowing that someone has been waiting for them there. I still ask myself who’s waiting for me, if there even is someone (or something) on the other side of that indecipherable woodland. I stay, just in case. I’m still here.

Who have been, or still are, your role models within the world of literature?

I remember reading John Kennedy Toole without understanding a thing but thinking that I wanted to do the same: create a character and draw their particular world. Then came poetry to help me find my centre (Marina Tsvietáieva and Anna Ajmátova are lighthouses for me) and theatre to help me lose it (Wajdi Mouawad, who I owe my writing to). Then there’s wickedness and ambiguity, and that’s where Hélène Cixous and Clarice Lispector lead the way, alongside Maggie Nelson and Mercè Rodoreda. If I could meet someone I’ll never have the chance to meet, I wouldn’t hesitate: Boris Vian. And the horizons, which are admirations: Gloria Anzaldúa and Fernanda Melchor.

“I think I came to writing as someone who reaches an unknown place knowing that someone has been waiting for them there”

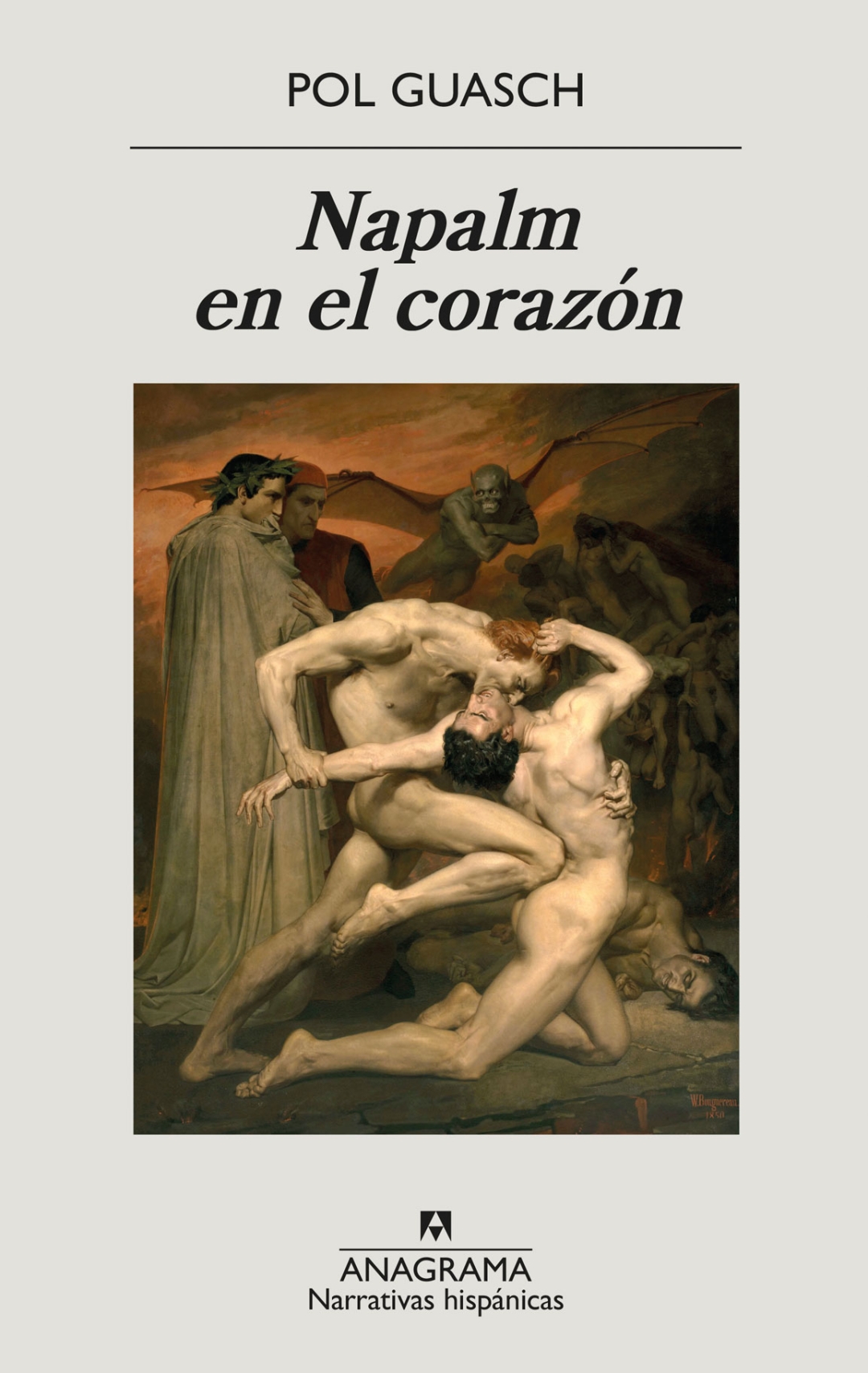

Until now, you’ve published a couple of poetry collections and a novel. What prompted you to take the leap towards prose with Napalm en el corazón? Did it entail a shift in tone?

There’s no change in register: there’s a shared understanding of the pleasure of the text and coming to writing. Each poem is a novel and I think of this novel as a really long poem that was with me for a really long time.

You’ve been granted the Festival Eñe Talento a bordo Award, which seeks to recognise the talent of emerging writers. What does this mean to you?

An opportunity to draw attention to peripheral poetics, both because of the language it’s narrated in, Catalan, and the form of writing that seeks to serve, and is deliberately complex and kaleidoscopic.

Cover of ‘Napalm en el corazón’, writer Pol Guasch’s first novel. © Anagrama

As well as talent, what else do you need to write?

Hard work, perseverance, despair, the will to carry on and enjoy yourself a lot, the belief that you’re invincible, the knowledge that you’re tiny, more enjoyment, and always, always, being an amateur.

The jury has singled you out as an author that “doesn’t lose sight of generational conflicts”, but your writing isn’t obvious.

To talk about the world that surrounds us, there’s no need to transfer references to a novel that becomes a mirror of what happens around us. We can write the world, pointing it out from the perspective of difference, of what it is not. That’s what I try to do. I’m happy that the jury considers it a distinctive feature of my writing.

Has also highlighted your “experimental audacity”. Do you like playing with language?

Starting out writing what the norm considers “poems” taught me that language isn’t only the subject of my work and my condition of possibility, but also my ultimate goal: the place I want to get to and where I’ll never fully arrive.

“Language isn’t only the subject of my work, but also my ultimate goal: the place I want to get to and where I’ll never fully arrive”

You write in Catalan, a language that, together with Basque, will be present at the Eñe Festival for the first time. What do you think of the initiative?

Comes late.

You travel reciting your poems; is literature a meeting place for you?

Absolutely. I remember how in South Africa poems were applauded and cheered; the feeling of community was incredible. But, fortunately, it’s also a space for discussion and disagreement. I think about the conflicting opinions that a novel can generate, for example, because dissent is a beautiful and painful way of finding yourself.

Finally, where do you look for inspiration when you need it?

I open a well-loved book, read an underlined sentence and think that I wish that I’d written it. If I can find the way to embrace it, I start writing. If not, I let it go.