Agustín Fernández Mallo

Heraclitus, Radiophysics and ‘Sálvame Deluxe’

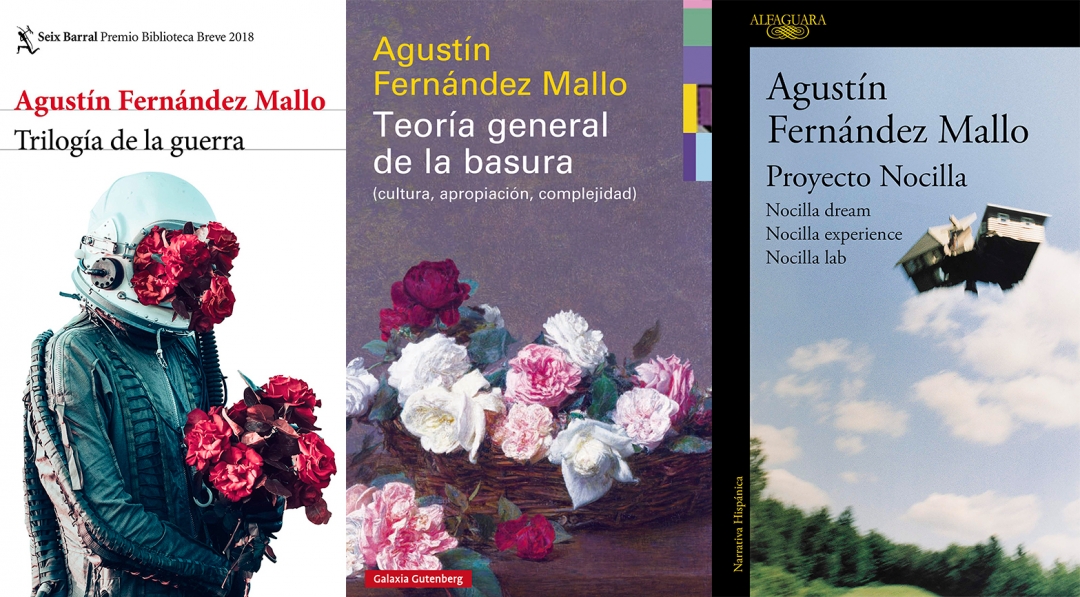

Agustín Fernández Mallo has been translated into more than ten languages, which is clear evidence of the relevance of his work. Last year he published two new major books: the novel 'War Trilogy', which won the Premio Biblioteca Breve, and the essay 'Teoría general de la basura' (General Theory of Rubbish: Culture, Appropriation, Complexity), a fiction book and a non-fiction book respectively in which Mallo, a flag bearer of the Nocilla Generation, expresses his personal vision of history.

In the mid 2000’s, Agustín Fernández Mallo (La Coruña, 1967) revolutionized Spanish literature with The Nocilla Trilogy (Alfaguara). Combining a scientific outlook with fantasy and lyricism, he continued writing, but this time turned —as he himself says — into a poet who writes novels and essays. In early 2019, The Nocilla Trylogy was published in the United States by the prestigious publishing house Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, which is no small feat.

Where does your vocation as a writer come from?

Writing comes to me through science and the need to explore the world by means of literary language. I wanted to create a world and contemplate it from the vantage point of literature, to create a system that describes our reality or invents part of it in order to understand ourselves better. This is, in fact, an investigative question, or philosophical, if you like. At first, I believed this could only be done through poetry and, somehow, I still believe so, but I’m not that extreme anymore.

What makes you think like that?

There is a verse in one of my poems that says: Poetry is not literature / If anything, it is the science of it. As a matter of fact, I think poetry is science. Lucretius's great poem, “On the nature of things”, is studied in poetry because it was written in verse, but it’s actually a science treatise. It was written in verse because back then everything was written in verse. When I read Heraclitus and other poets, I see they make questions about the first causes of things. When Newton wonders why an apple falls and the moon does not, he’s posing a question that could perfectly be part of a poem.

In 2006 you published your first novel, Nocilla Dream, which became a literary phenomenon. How did you experience that moment?

I wrote that novel without having a clear idea of what I was writing. I think it’s important to never know exactly what you’re writing because that means you’re experimenting with something that might be good or new. I finished Nocilla Experience and Nocilla Lab thinking nobody would want to publish them. What happened then was a gift. I realized the literary world was looking for a renovation and, somehow, I fulfilled that expectation. As my friend Eloy Fernádez Porta said, what I did was to manage complexity in a unique way, that is, without realizing it. Back then I was working as a radio physicist in a hospital. Working fifty hours a week with patients makes you come back down to Earth. I travelled and gave interviews, but the next day I had to be at the hospital dealing with clinical cases, and that is inconsistent with thinking about literary success.

“I think being uncultured starts by thinking only what is supposedly excellent or cultured can offer something valuable. I have extracted verses from cheap TV shows such as McGyver or Sálvame Deluxe”

A few months ago, The Nocilla Trilogy came out in the United States. How does the English-speaking world relate to it?

In a very different way. They focus a lot on the part concerning their culture or say it’s like the B side of the great American novel. They say things that I don't quite understand because it’s a different culture. They also read it from a political perspective, more than Spanish speakers do. Their reading is more severe and analytical, less ludic. They don’t take the fantasy part into account so much, although they love everything about Borges, he’s a model for them. But I’m delighted because it was very well received. It was reviewed by The New York Review of Books, Harper’s Magazine, and The New York Times, which is rare for a translated Spanish author. The English-speaking market doesn’t translate a lot—only two percent of the books in American bookshops are written in other languages.

Other than in literature, where do you draw your inspiration from?

Television, with and without sound. I think being uncultured starts by thinking only what is supposedly excellent or cultured can offer something valuable. I have extracted verses from cheap TV shows such as McGyver or the [Spanish TV show] Sálvame Deluxe. Then you tend to be able to use it in the right context. In Teoría general de la basura I say that thinking only excellence is worth it can block you. The world is organic, and in order to create the fact that there’re symbolic excrements in it can’t be ignored. I like television very much because of that. I find something in all the programs I watch. I don’t understand why there are so many intellectuals who despise television. One day [writer] Juan José Millás told me that television had saved his life many times. Same for me!

‘War Trilogy’, ‘Theory of Rubbish’ and ‘The Nocilla Trology’, by Agustín Fernández Mallo. © Seix Barral, Galaxia Gutenberg and Alfaguara publishers

What is the basic approach of General Theory of Rubbish?

What this book suggests is that creations that remain and interests us are not the ones that have been made based on the excellence of previous works, but from residues. A clear example is Cervantes. He didn’t care so much about the excellent chivalry books that preceded him, although he did know them. He used the residues in those books, the rubbish of his time, and with them he created a new genre in El Quijote. I was very interested in reconceptualizing the term "rubbish" because changes come about when the meaning of a word we’ve always heard changes, creating a revolution.

Is War Trilogy a novel that addresses political issues without being a political novel?

For me it’s more about an anthropological investigation: where does the human being come from, what unites us, what separates us, the fact that we are all connected to a war casualty. It raises the issue of migration or why half the planet wants to come to live in Europe. How the Syrians land on European coasts while Europeans strive to destroy Europe through nationalisms. The novel focuses on the fact that the classic ideological divide of the left and the right is being diluted; people no longer vote based on ideology but on identity.

What is talent for you?

Talent for me is someone's ability to make us see what we have always seen but in a way we have never seen. Seeing the world as if you were an alien who has just landed on Earth. When Proust has a bite of that madeleine cake, we see it as nobody had ever seen it before. Newton talks about an apple like no one else had done before. And all these things are present in our everyday life, you don’t need to go to Orion to perceive them.