Almudena Alberca

Much More Than a Nose

The first woman in Spain to be named Master of Wine represents a new generation of winemakers who preserve the legacy of the past while working on the challenges that wineries will face in the future, the main one being the adaptation of grapes to climate change.

Almudena Alberca (Madrid, 1978) is the first Spanish woman to be named Master of Wine, a title awarded by the Institute of Masters of Wine, located in the United Kingdom, whose aim is to bring together international excellence. Only 380 people in the world ––131 of which are women–– have passed a demanding examination to achieve this recognition, which entails years of study, research and analysis of colours, flavours, and smells. They are the elite athletes of wine, capable of identifying varieties from anywhere in the world in blind tastings. Sensory analysis is complemented with a thorough training on production models and international operation in order to know and distinguish different geographical areas with their own challenges and peculiarities.

Alberca, who has a BA in Oenology and a MA in Viticulture, has over 15 years of experience in winemaking. She took her first steps as an oenology assistant at Bodega Viñas del Cenit in Zamora, participating in the creation of the award-winning Cenit 2009. In 2015, she was named technical director at Bodegas Viña Mayor (Valladolid).

Where does your passion for wine come from?

My grandfather owned a small vineyard for family consumption in the Arribes del Duero area. As a child, whenever we went to the village, we helped them out in the orchard or in the vineyard. I remember stepping on grapes and the moment my family bought a manual crusher destemmer. However, as time went by, it became more and more difficult to maintain the vineyard. I’ve always been interested in the world of food, so I studied Agricultural Engineering. I was attracted by the farming and the food industries and when I discovered the world of wine and got hooked on it.

After specializing in Oenology and Viticulture you continued your specialization in New Zealand. What surprised you the most about their techniques?

They work differently. I’d highlight their respect for perfection regarding aromas and taste. They make sharp, defined wines. You can tell in international blind tastings because they have a very clear personality, a “taste of place”, which comes from their way of using grape varieties. In Europe we think what we do is unique, but everything has already been written, there are no great breakthroughs. They organize conferences about Sauvignon Blanc, for example, and, with great honesty, all experts share their experiences, the problems they’ve faced and how they’ve addressed them. They learn a lot and return home with that shared knowledge. We could learn from that generosity and honesty.

Apart from a good sense of smell, what other talent is required to be a good winemaker?

A winemaker must be multidisciplinary because they’re the ones who create the nuances, deciding on every step, from the choice of the vines and the life of the grapes in the vineyard, to the bottle that reaches the final customer. A winemaker influences the taste of the grape, decides on how long to age the wine in barrels, on all the prior preparation. Everything is based on the senses, but that must be supported by knowledge of biology, physics, and chemistry. It’s all very studied, very scientific, so that they know what’s happening to the wine in every step of the process. A winemaker must also be able to transmit and explain wine in a universal language everyone in the winery can understand, from the technical and marketing teams to the general manager and the customers. If you aren’t able to communicate, your work gets wasted.

“You have to take great care of yourself and your health before the tasting. You must be in top form in order to identify as many nuances as possible. In fact, not getting enough sleep affects your tasting ability”

How would you explain what a tasting is about to an inexperienced person in a way they can understand?

I think that the complex language of wine should only be used by the sector’s experts. No one is born ready to run a marathon — that’s something you achieve through training. And the same goes with tastings. We all have that ability, but someone must teach us. It's like a perfume: what does it smell like? Musk, wood, citrus? Young people use vanilla, coconut, wild fruit fragrances, and we’re all able to identify the nuances, but it’s harder to describe a complex perfume. Separating the scents is helpful in this case, but you need someone to teach you how to identify them.

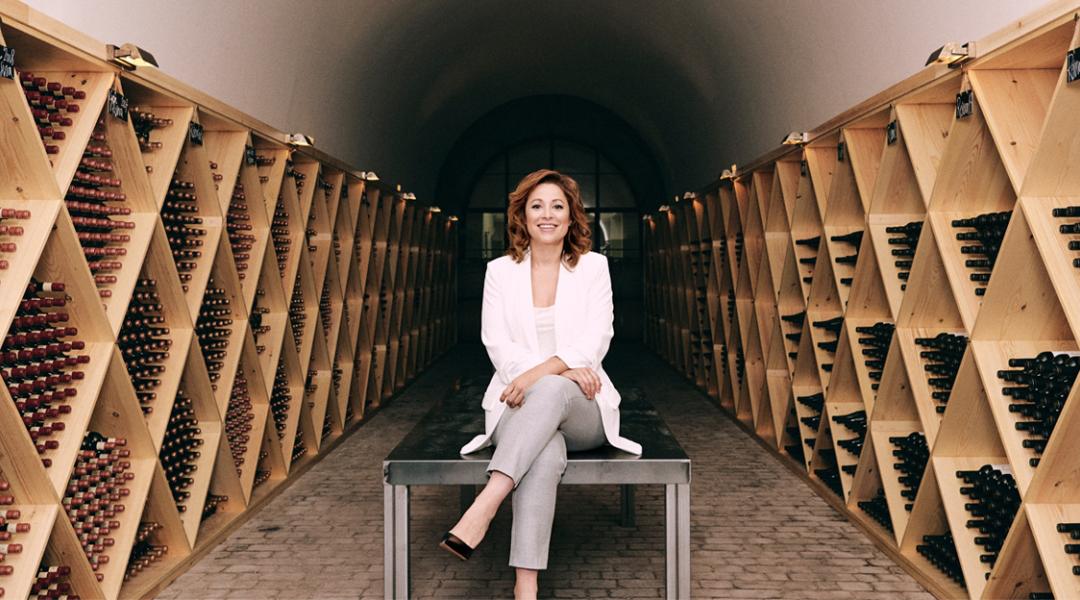

Almudena Alberca in its natural habitat. © Belén de Azcárate

You are the first woman in Spain to be named Master of Wine. What has this title contributed with to your career?

It’s been a source of personal fulfilment because I achieved my goal. I’m very happy now, but the training was hard, both theory and practice. You go through difficult times and adversities that can only be dealt with if you know yourself very well. One of the biggest challenges was perhaps to express myself and be competitive in a different language. The blind tasting was also very intense because you have to identify all wine styles and areas in the world, and that requires a thorough training. As everything depends on the senses, before the tasting you have to take great care of yourself and your health. It’s as if you were an elite athlete — you must eat and sleep well and be in top form in order to identify as many nuances as possible. In fact, not getting enough sleep affects your tasting ability.

How do you imagine the world of wine in Spain in twenty years from now?

I think that, at a technological level, we’ve already passed the phase of industrial revolution and now we’re going through a phase that consists in discovering the terroir, the varieties of each area, the microclimates, and so on. Our particular orography separates different wine areas, which have different climates, that’s why the goal is to discover and classify soils by region. In general, as the world becomes more and more globalized, the secret will be in the search for identity and honest wines.

“As the world becomes more and more globalized, the secret will be in the search for identity and honest wines”

How will climate change and extreme weather conditions affect Spanish wine?

Unfortunately, we can’t make reliable predictions yet. As for water deficit, droughts, and high temperatures, Australia is a little more advanced because it has serious problems with that. There is no solution against climate change, but commitment to sustainability is a global concern in the world of wine. This means that you can use certain resources to alleviate the adverse effects of the weather, that you can take care of the soil by managing the vegetation and protecting biodiversity, by installing buried irrigation lines and introducing more sustainable practices. The complexity lies in how fast climate change will come and the steps we should take based on that. Drones and remote sensing can be used to monitor soil conditions, oxygen consumption, humidity. There’s a lot of potential for development in that regard in terms of trained scientific and technical personnel. I believe that a country like Spain, with agriculture as part of the economy, can advance successfully in the fight for climate adaptation of the wine sector.