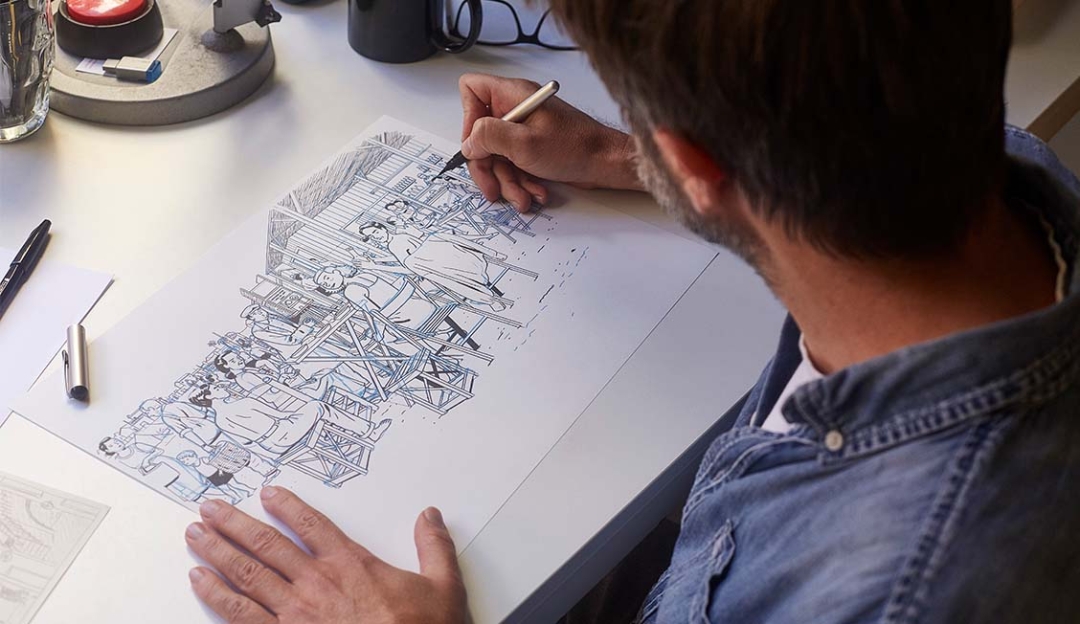

Paco Roca

The outline of memory

The success of 'Wrinkles' changed Paco Roca’s life. Since then, he has become one of the leading illustrators within the world of Spanish comics, recently receiving the Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts. His artistic talent allows him to combine the sharpness of his drawings with a narrative inquisitiveness that lead him to explore our most recent history — as well as his own— and defend the nobility of many anonymous lives.

After years publishing in magazines like El Víbora, the third book of cartoonist Paco Roca (Valencia, 1963) —Wrinkles— became a turning point in his career. The work was turned into an animated film under the same name, directed by Ignacio Ferreras, which granted the illustrator a Goya Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. From that moment onwards, each new project has enhanced his artistic prestige. His latest comic, Regreso al edén [Return to Eden], is a journey to post-war Valencia and is based on experiences from members of his own family of an era that was extremely tough both politically and socially. Until the 24th of April, La Nau Cultural Centre in Valencia is home to an exhibition based on photographs and documents related to it.

Did you choose to draw, or did drawing choose you?

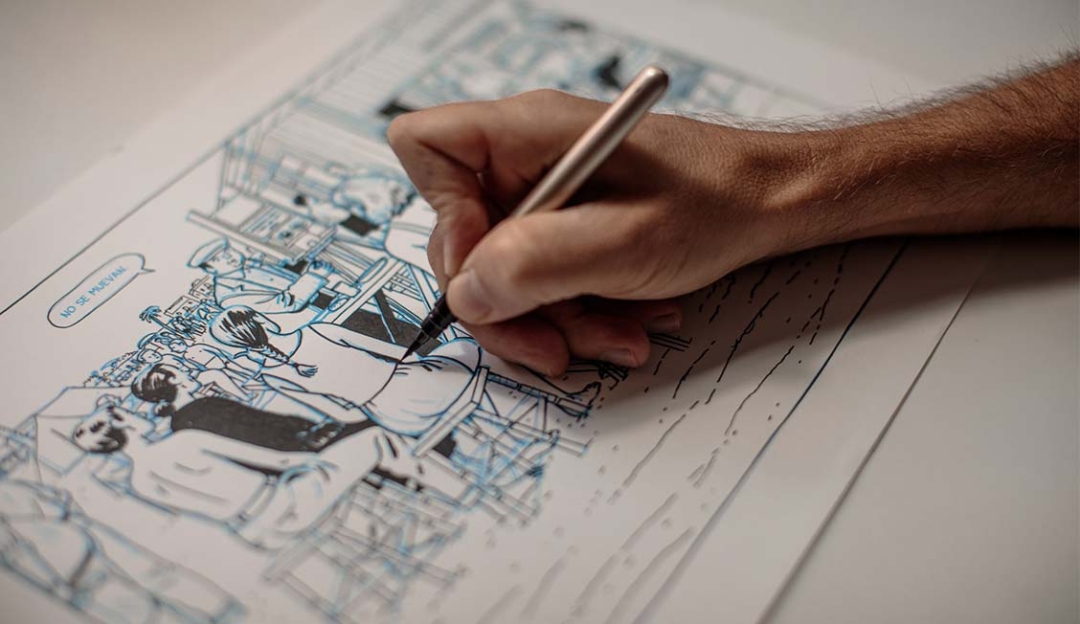

It all came from a need to tell stories. If I’d been good at writing, perhaps I would have written them, but I was good at drawing. I grew up in the 1970s, so all I needed was paper, some markers and pencils. That was enough to tell any story, and this is still how I work today.

In 2012 there was an exhibition on your work called Dibujante ambulante [Travelling illustrator], does this concept define you as a creator?

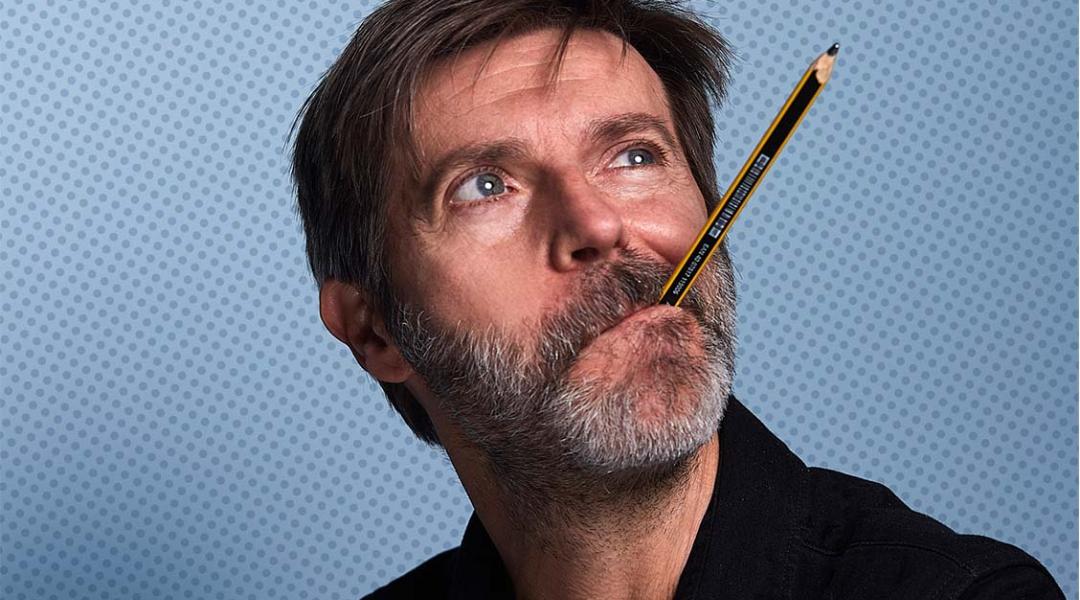

For a long time, and until the pandemic, that was indeed the case. Until 2007, I lived quite a quiet life, I finally had time to draw, but then Wrinkles came out and changed everything. Since then, the weeks where I haven’t had interviews, ceremonies, trips... have been few and far between. When I could finally live off comics, I started having less time to draw them. As someone who loves the act of drawing, it’s been hard for me to find a balance between continuing to create and being that travelling illustrator.

“When I could finally live off comics, I started having less time to draw them”

What you’re saying sounds kind of ironic...

The change brought about by the warm reception of Wrinkles was quite sudden. Until then, nothing I’d ever made had had such a big impact. Drawing didn’t bring me any money, I lived off of advertising and worked on my comics in my spare time. Because of the theme it touches on [the main character is an elderly man with Alzheimer’s], I didn’t think that Wrinkles would change my career, but when it came out in France it worked well there. Later, also in Spain, and then I won the Barcelona International Comic Fair Award, the National Comic Award... Within a year, my personal and work life drastically changed.

You’ve said before that your work consists of telling stories and trying to understand the world.

I think that, as Picasso used to say, art allows creators to get to know the world. Also, I’m lucky in that the type of comic I draw is very personal. Through my work, I can show what I’m concerned about, I’m not restricted by assignments. That’s why I reflect on what’s happening around me and, along the way, I get a better understanding of myself. I’m also fortunate because many readers fancy reading what I fancy drawing.

In the end, drawing cartoon strips is also a kind of therapy...

For me, comics aren’t a way of communicating a certainty, they are the path that lead me to understand something: a topic, a character... And that journey, from the moment you start to work on the story until you finish it, changes you.

Which is the story that has moved you the most?

My comics aren’t usually very cheerful, so they all move me in some way. For Wrinkles, I conducted some field work in nursing homes which was tough at times. Some parts of Twists of Fate or The House were also hard to draw, in that case for personal reasons, because my father had just died. But, in the end, they are rewarding experiences. The more honest you are, the more you expose yourself, and the more you overcome shame, the greater the reward, because the work reconciles you with yourself or with your past. And readers end up seeing more than what you put into the story.

In 2021, you were awarded the Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts, have you become one of the headliners of Spanish comics?

It depends what you focus on. I’ve had a stroke of luck that gives you certain visibility within Spanish culture, but there are authors who have a bigger impact in other countries, like Ana Miralles in France. In my case, it helps me reach a larger audience, other areas within culture, TV, the press, museums, literary fairs... It’s true that, thanks to awards such as the Goya Awards or the Medal, comics transcend their own field, but we have to remember that there have been other illustrators in the past who have also been granted this kind of recognition.

“For me, comics aren’t a way of communicating a certainty, they are the path that lead me to understand something”

Wrinkles became an animated film and, more recently, Alejandro Amenábar adapted El tesoro del Cisne Negro [The Treasure of the Black Swan] to create La Fortuna. Does it feel odd to witness these types of transformations?

In the case of La Fortuna, it came completely by surprise. I admire Alejandro a lot and to think that someone like him, who could adapt any book or comic —or write his own stories—, has taken notice of something I’ve made lifts my spirits. It’s also interesting to see how a story can be told in a different way: you choose some elements and place them in a certain order, but then someone like Amenábar comes along and takes that apart to create his own version. I think that the worst thing that can happen to any author is to be too endogamous; you can learn a lot from other disciplines.

What other projects are you working on at the moment?

I’ve been working on a story about Cat Woman set in Spain for some time. The way DC Comics works is very slow, and they’ve taken so long to give the script the go-ahead that I’m caught up in another project. It takes place in 1940 and is a work on memory. It’s based on a true story about the White Terror, because when you get into chapters of the Civil War and the Franco regime, the stories are endless. I’m making it with El Mundo journalist Rodrigo Terrasa and that’s what I’m focused on. I don’t feel like working on Cat Woman right now, I want to finish this story first.