Avelino Sala

Art with speech

His social environment is his inspiration and, from there, he artistically specifies his own reflections. His versatility also allows him to give his work radically different looks between exhibitions. The talent of conceptual artist Avelino Sala reveals itself again at Estampa 2022, showing some of his pieces, and the Lanzarote Art Biennial, where he presents his ‘Museo Arqueológico de la Revuelta’.

Avelino Sala (Gijón, 1972) assures us that his homeland of Asturias has shaped 100% of his personality. Perhaps the mountains have granted him a strong and good-natured presence, although critical of what doesn’t work socially; and perhaps the sea has given him, since a young age, that sense of freedom that he projects onto his artwork today. Freedom that he also experiences personally when he practices one of his greatest passions: surfing. “It’s my way of restarting my mental hard drive. A moment of utmost joy: more endorphins are released, and I have the feeling that everything is fine,” he shares.

Sala is also swell on land, specifically, at art galleries and festivals. In fact, he’s currently exhibiting at the Lanzarote Art Biennial (until the 2nd of November) and at Estampa 2022 (from the 13th to the 16th of October in Madrid); and before the year is out, his radically hued pieces can also be seen at Swab Barcelona Contemporary Art Fair, Pinta MIAMI, and Abu Dhabi Art Fair. A last quarter that presents itself full of work with one of his most anticipated projects: En busca del Milagro, an unpublished installation that won him the Premio Museo Barjola 2022 in Gijón and was specifically designed for the Capilla de la Trinidad in the same building.

Different social episodes are the driving force behind your work. Where does this political interest come from?

It's not interest in politics itself, but rather in the current social and historical context that allows us to analyse our environment as beings capable of the best and the worst. And in this sense, art is a reflective tool with the ability to promote thought and generate critical mass, allowing us to see things from different perspectives. Because there are other narratives, beyond the official ones, other stories and other ways of understanding our past and our present.

Is art like resistance to power?

At least as an essential tool to make us think. During such globalised, accelerated, and misinformed times, art is a fundamental space to discover and get to know ourselves from a different perspective, perhaps a calmer one. Whether that can be a lever to resist factual powers is up to each artist and each audience.

“Art is a reflective tool with the ability to promote thought and generate critical mass”

The rocks in your sculpture installation Museo Arqueológico de la Revuelta exhibited at the Lanzarote Art Biennial are also a symbol of resistance. What do they tell us?

It’s a chronicle of the present —of the crises of our time, of the failure of official narratives— and a blueprint of resistances. A catalyst of important moments that become part of the museum in the form of rocks. If archaeology studies civilisations through the tools and instruments of the past, in this case it does so through these rocks collected at modern-day riots. This is an archaeological overview of the present, somewhat of a paradox.

Out of all those rocks, which is the most meaningful for you?

Because it was the seed of the project, perhaps a sampietrini [cobblestone] from Rome that I picked up after a demonstration in 2010, when I lived there thanks to a grant from the Spanish Royal Academy. Although, beyond the stone itself, what matters is the idea behind it, that summary of social and political issues. They come from extremely diverse historical moments connected to outrage movements, racist crimes, or social battles, as well as feminist protests, against inequality or against climate change. The particularity of this work is that, unfortunately, it keeps growing, because every year more stones are added.

Why are the terms “dystopia”, “utopia”, or “collapse” so important in your artistic discourse?

Because they’re a symbol of our time, and I believe that artists have the responsibility to be involved in the context that we live in and to talk about the things that surround us and concern us. I’m not at all interested in the pursuit of beauty itself, or that more outdated view of art. I believe that artists must find the balance between discourse and aesthetics because we can talk about the toughest or the most heinous using poetic and beautiful tools. The work of art is in that balance.

Must they inevitably go hand in hand?

Yes. Harmony between discourse and aesthetics is pure balance; if it’s lost, the work fails. Art is a tightrope balancing act.

You let artistic processes flow, without obsessing about the technique or the results of the work. But is there a previous mental process at least?

It’s true that I don’t really care about the final format as much and that processes often differ depending on the location and type of work. Some processes are slower, requiring more research, and others are more direct, on first impact. Mentally, yes, there are extremely rigorous processes, although they are also intuitive because creating is closely related to intuition.

“Artists must find the balance between discourse and aesthetics because we can talk about the the most heinous using poetic tools”

In Distopía/Utopía you presented watercolours, in Rebelión en Asturias you used mock-ups and even photographs printed on feathers, in Tradición vs Historia you played with books and small sculptures, in Naturalezas Muertas your material was nature itself... What leads you to choosing a specific form?

Forms arise naturally and, as we were saying, intuitively. How to shape an idea emerges in relation to many factors that condition each project, like the space it will occupy or if people will participate or not, among others. There are thousands of conditioning factors that make, for example, a work take shape as the projection of an interview alongside a series of documents related to the Prestige catastrophe [a collection that was part of Naturalezas Muertas], or as images full of visual information and aesthetic potential, like in La pluma y el olvido.

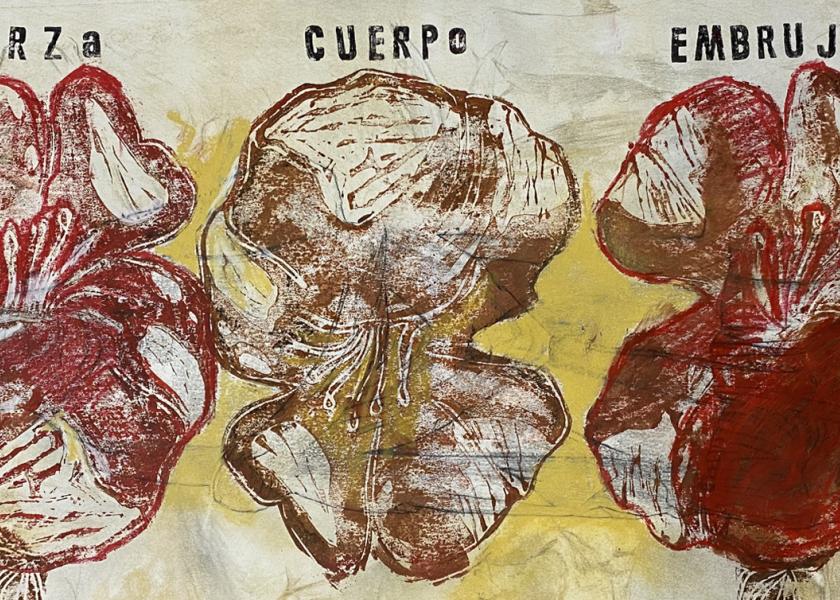

Image of the exhibition ‘Beyond Words’ (Galería ADN, Barcelona) that included several works by Avelino Sala. © Roberto Ruiz

One of your obsessions is interacting with the audience. Why?

Because a work must communicate; if it doesn’t generate that exercise of conveying ideas and reflections, it doesn’t work. Art is usually described as something cryptic, hard to understand by the audience. If that is so, the artist is responsible for trying to make it easier to understand, so that it is conveyed clearly and is understandable. If the audience doesn’t react, the work is no good.

Work of art, object, demonstration, project, complaint, reflection… Which concept would you use to define what you do?

Without a doubt, the first. Everything we artists do falls under the category of work of art.

As well as editing Sublime magazine, made by artists and which works as a platform for art and social criticism, you also work as an art curator. Does curating the works of others force you to reconsider your own?

Curating is something extraordinarily complex that requires a lot of research and study. And, indeed, it’s a healthy exercise because by curating you abandon your own work to try to highlight the work of another artist. In the end, it’s an exercise of sharing and learning from others.

All your work is serious and committed, but at the same time it’s really ironic. Can an artist like yourself live without humour?

No. A good sense of humour is essential in life. Being able to laugh at oneself and not take yourself too seriously is very healthy.