Marina Perezagua

“Writing allows me to live with my characters”

Marina Perezagua is able to swim across the Strait of Gibraltar in four hours, and to write novels like ‘Yoro’, ‘Don Quijote de Manhattan’, and ‘Seis formas de morir en Texas’ in four years. Writing, diving—two ways of looking inside oneself, of fighting against the speed of the world. She has been living in New York for over fifteen years, and her cosmopolitan nature permeates in her stories, set in faraway but recognisable and well-researched places.

Marina Perezagua (Seville, 1978) has a degree in Art History from the University of Seville and a PhD in Philology from the State University of New York. She is the author of two short story collections (Criaturas abisales and Leche) and two novels (Yoro—Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award for the best novel written by a woman in Spanish—and Don Quijote de Manhattan), in which she already showed unusual audacity as well as an extraordinary ability to make up stories and tread on complex, often uneasy literary territories. All these premises and all that talent are confirmed in Seis formas de morir en Texas, her first novel for the Anagrama publishing house. Owner of a particular and unique universe, in this new effort Marina Perezagua once again displays the obsessions and stylistic qualities that established her as an essential voice in modern Spanish fiction.

Two families, two continents and a plot about organ trafficking give Marina Perezagua the opportunity to bring into play a series of characters whose fates are bound by a beating heart that has given life to several people. Told through the eyes of different characters, a plot unfolds in which revenge, love and guilt coexist, keeping the reader in suspense from the get-go.

The relationship between parents and children is very present throughout the novel, is that intentional?

Actually, I have no conscious intentions when I write. But it is true that the parent-child relationship is very present, not only in this novel, but also in my previous books. I imagine that by telling a story about characters who live on different continents, family relationships act as a symbol of that communication with ‘the other’.

In the novel, we find characters as polyhedral as Robyn’s; an American teenager, blind, irascible, who expresses herself through letters and is on death row after having killed her mother. What sparked the idea for this novel? An image, a news item, a memory?

A story: that of Damien Echols [of the West Memphis Three], who entered death row as a minor and got out a few years ago, when he was proven innocent after having spent eighteen years locked up without seeing daylight more than once. But what caught my attention the most was his kindness, despite the humiliation and torture he’d been subjected to half of his life. I think that kindness is also important in my novel.

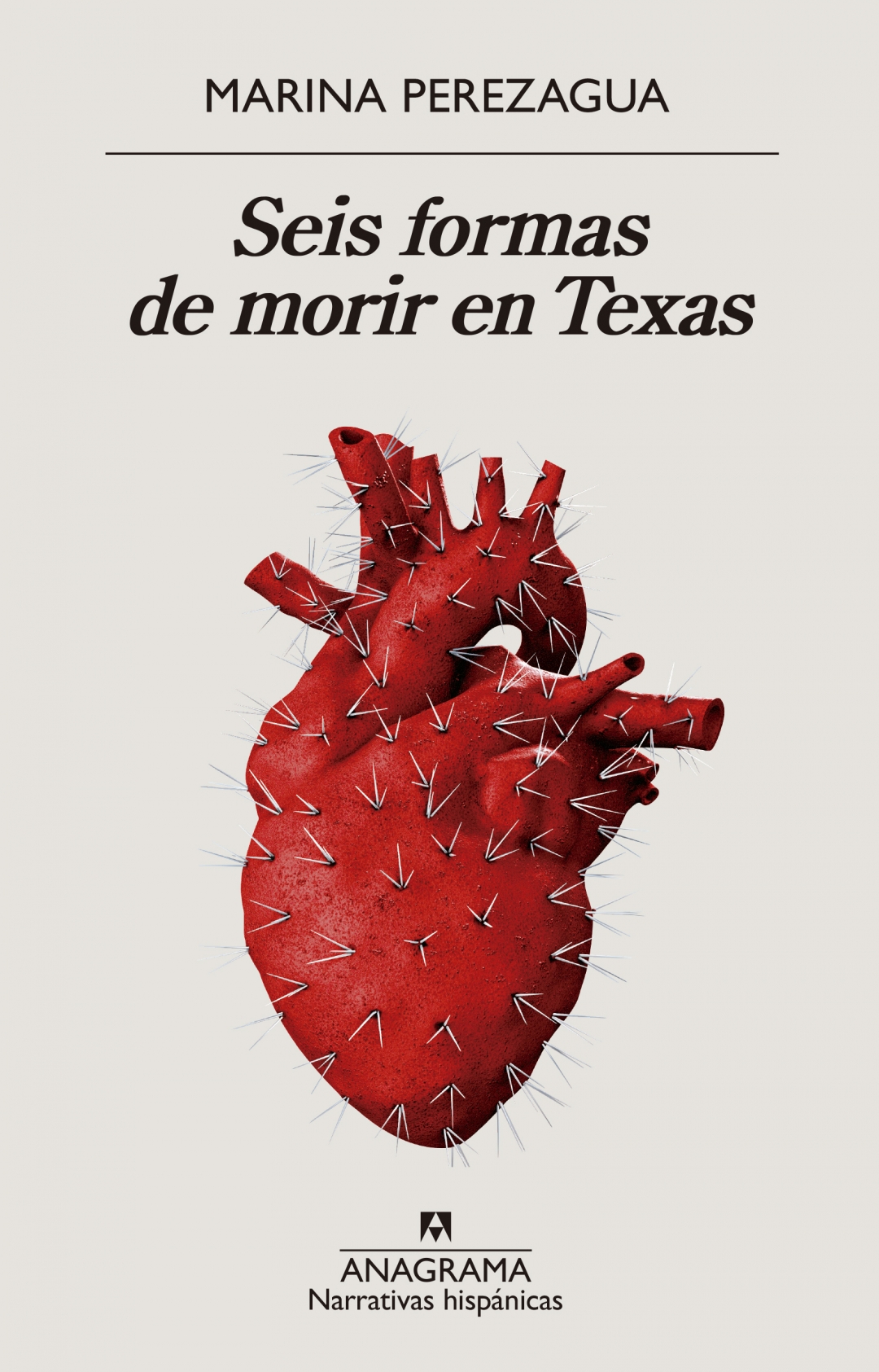

Cover image of ‘Seis formas de morir en Texas’ by Marina Perezagua. © Anagrama

How did you come up with the idea to incorporate such an unusual topic as organ trafficking?

The reason is literary. I needed to find out how someone could be taken off death row, but by somewhat extravagant, though plausible, means. Then I discovered the horror of what began to happen in China in the 1990s and that continues today. Hundreds of thousands of innocent people are killed in order to remove their organs and sell them to patients, usually foreigners. The horror is even greater when you think that it’s the Chinese Communist Party itself sustaining this mechanism to feed the funds of its healthcare system.

You are a great creator of images, with an unquestionable ability to tell a story. How important is style to you?

Extremely important. Actually, I’m meticulous in everything concerning the literary factor. I’m patient and I don’t mind working on a paragraph for as long as necessary. The content is important—to really have something to tell (and to me that’s the starting point), but without style there would be no literature.

It is often said that a writer’s tools are memory, imagination and constancy. In your case, for example, the death row inmates’ testimonies are inspired by several documentaries on the matter. Should we also add research?

Yes. The relationships between the characters are always fiction, but the scenarios are fully documented.

Your stories are usually quite realistic, your subject matters are disturbing, and your characters rather peculiar; is there room for improvisation in your creative process?

Yes, but in my case the level of improvisation depends on the tone. There’s much more room for it when the tone is lyrical—in the epistolary relationship between the main character and her lover, for example.

“The sea is an oneiric space. Many of the stories come to me when I’m swimming; it’s like remembering the stories I dreamed in detail”

Why or for whom does Marina Perezagua write?

I’m not sure. I think I write in order to live with my characters during the time I’m with them. I don’t really write thinking about the reader, because there is no universal reader. And even if I wanted to, I can’t please everyone. That’s why I try to think about the story and enjoy the process.

We know that you live in New York and that you are passionate about the sea, that you like swimming and diving, and that you are able to swim across the Strait of Gibraltar in four hours. What has helped you more in your career as a writer, swimming or traveling?

The water, definitely. In the water I feel I am where I’m supposed to be, and many of the stories come to me when I’m swimming, probably because I’m more relaxed. The sea is an oneiric space. For me it’s like dreaming and remembering the stories I dreamed in detail.